This is Part 3 of a multi-part essay written for my “Pathless Travels” column. It was originally published in Northern Weekly Dispatch, 14 Aug 2005, and which I then reposted a few months later on my defunct blog hosted at Blogspot. Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, and Part 4 here.

The year was 2005, and the GMA broadcast network had scored a big hit with the sword-and-sorcery TV series Encantadia. Sword battle movies were on the comeback trail worldwide, from Hollywood to China, and the genre seemed to appeal to Filipino sensitivities. But are they really unlocking insights to our own history?

In most countries, the collective past is painstakingly preserved in history books, research publications, archives and museums. There are monuments, restored ruins, tombs and landmarks, paintings and prints, bas reliefs, dioramas. There are even live and filmed reenactments, usually on the very sites where memorable events happened.

Some of the most romanticized events and figures of a nation’s history, rightly or wrongly, have to do with wars and revolutions. It is as if the emergence of a nation or hero required bloodshed, like a person’s birth and passage to adulthood.

This is understandable. After all, most nations were actually born and steeled into maturity in the throes of such violent crises. Many national heroes have emerged as leaders in such conflicts.

The problem begins, however, when the public is fed mostly with over-romanticized notions of war and combat heroics, while only the military establishment is given the chance to study real strategy and tactics.

It is one thing to romanticize armies and wars of the olden days. It is another thing to educate the public in military science and history so they can cope better in a real war.

###

Take for instance Scottish national hero William Wallace and French national heroine Joan d’Arc, and their roles in their countries’ respective wars of liberation against English occupation in the Middle Ages.

Braveheart, a cinematic portrayal of the Scottish struggle, and the two Joan of Arc films I mentioned earlier, despite their historical inaccuracies, are welcome enough for starters, if you want to satisfy your incipient interest in war history. Notice, though, that these are cases where the heroes loom much bigger in real life than in the romanticized Hollywood versions.

Try to do an Internet search on the two historical figures, Wallace and Jean d’Arc. You’ll be amazed at the tremendous amount of historical detail available, whether online or in libraries, archives and museums, about their exploits as real-life political and military leaders.

The actual battles they waged and won are analyzed in terms of battle formations, weapons and tactics. Their battles are also analyzed in the context of the entire war and their impact on the wider theater of politics.

###

As Filipinos, are we exerting the same effort to study in detail the history of our own nation’s wars and revolutions? Do we have a comprehensive picture of how our ancestors battled foreign invaders with indigenous weapons and tactics? Is this knowledge being popularized in films and other mass media?

For example, how much do we really know about the tactics and weapons with which Lapu-lapu waged and won the famous Battle of Mactan? Have we separated hard documented fact from mere speculation and outright fiction? Lapu-lapu was supposed to have instructed his men to strike at the joints of Spanish soldiers, where their armor was weakest — is this a documented fact or a self-reassuring factoid?

Through a quick check of sources, I realized that there are several extant eyewitness accounts of the Magellan expedition, yet the only popularized account of the Mactan battle is that of Pigafetta, the expedition chronicler.

Aside from its obvious colonizer’s bias, Pigafetta’s account is so sparse in detail that some would doubt if he really witnessed the battle; perhaps he simply wrote down what Magellan’s surviving lieutenants told him.

###

Nevertheless, even without detailed accounts of battles against the Spanish invaders, we could still try to reconstruct our ancestors’ military capacities. We could use other methods of history and archeology, such as those employed in Scott’s Cracks in the Parchment Curtain.

In his book Barangay: 16th Century Philippine Culture and Society, Scott actually devoted an entire chapter on this subject, “Weapons and War” (in Part One, The Visayas) and substantial sections as well in other chapters.

But the question remains: how much of this is reflected in local story books, films, and websites? Not much, I’m afraid.

###

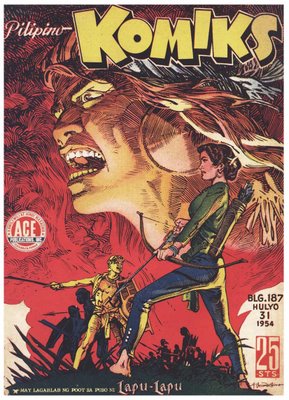

For some time now, I’ve been combing the city’s video stores and sidewalk stalls for a VCD or DVD of Lito Lapid’s 2002 film Lapu-lapu – the only cinematic account of the Mactan battle as far as I know (although I will welcome any correction about this).

Although a box office flop, Lapu-lapu garnered the Film Academy of the Philippines’ Best Picture award. Recreating an entire coastal village and a full-sized Spanish sailing ship and utilizing 3,000 extras, this lavish film was touted to be worth the P35 million it took to produce it.

Oddly, I couldn’t find a CD copy. Maybe I didn’t search hard enough. Yet, in almost every stall where I looked, there were rows of movie CDs about fake superheroes like Lastikman, Captain Barbell, and Anak ng Panday. But on Lapu-lapu, zilch. This only shows the local film industry’s awful sense of history.

###

My intent in reviewing Lapu-lapu was to check my own bias against most local films about pre-modern wars – insofar as we ever made films about pre-modern wars, anyway. We couldn’t even get the most obvious historical details right, such as what our ancestors wore for battle, what their war boats and weapons looked like, and what combat formations or ruses they adopted. (Author’s note dated 7 April 2012: I do appreciate recent efforts along these lines, such as in the recently-concluded GMA Network telenovela, Amaya.)

I expected Lapid to disprove my theory. After all, his film was supposed to have relied on research provided by the UP Department of History. But since I couldn’t find a CD copy, I had to rely on other reviews. Many of them were harsh; some wrote off the movie as a poor imitation of Braveheart.

Here’s a sampling from Ambeth Ocampo’s history column in the Philippine Daily Inquirer: “Lito Lapid was not wearing the historically correct costume. He carries a bad copy of a Kalinga shield when one can order a good reproduction and cheaply, from Baguio City souvenir shops.” More than that, Ocampo said, Lapu-lapu carried his Cordillera shield upside down. Ay apo, kababain.

But I’m suspending my judgment of the Lapid obra maestra until I get hold of a copy and watch it myself.

###

Meanwhile, should we urge local producers to ride on the recent “sword-and-sandal” hits from Hollywood? After Lapu-lapu’s box office dud, should we hope that another filmmaker will dare tackle the Dagohoy rebellion, or Sultan Kudarat’s exploits, or Amkidit’s resistance, or Raja Sulayman’s defense of Maynilad?

“I’m afraid I can’t wait that long,” says Kabsat Kandu, as he checks the time and channel for his favorite sword-and-sorcery TV series. The force of Encantadia is strong in my neighbor.

“But wait,” I tell him, hitting the TV remote back to the National Geographic channel, where a film reenactment of the classic Battle of Thermopylae is being shown. “There is hope on the horizon.”

###

In many Western countries, there are historical societies and military-style clubs that research ancient tactics and reenact battles of yore as realistically as possible. Often, their people are hired as military consultants, fight choreographers, or stunt crews for war films.

It is their fanatic passion for military detail that provides a cinematic realism so authentic that even director and crew are spellbound as the choreographed carnage unfolds before the camera.

I know at least one similar effort here. In the past few years, Lapu-lapu City (on Mactan island, now part of Metro Cebu) has held an annual reenactment of the Battle of Mactan. The cast is composed of 400-plus bit actors from Mactan barangays and arnis enthusiasts of the Mactan Island Eskrima Alliance. I heard they were also involved in the filming of Lapu-lapu.

Maybe local and overseas enthusiasts of arnis and its many variations, from ancient kali and pangamot sword-fighting styles, down to the modern sinawali, doce methodos and lameco escrima, should expand their efforts to include wider areas of native military science and historical preservation.

And that leads us to the concluding part next week of this over-extended romance with swords. #

One Reply to “Romancing the sword (3)”