This is Part 4 of a multi-part essay written for my “Pathless Travels” column. It was originally published in Northern Weekly Dispatch, 21 Aug 2005, and which I then reposted a few months later on my defunct blog hosted at Blogspot. Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, and Part 3 here.

The year was 2005, and the GMA broadcast network had scored a big hit with the sword-and-sorcery TV series Encantadia. Sword battle movies were on the comeback trail worldwide, from Hollywood to China, and the genre seemed to appeal to Filipino sensitivities. But does it really unlock insights to our own history? From our rich historical military legacy as a people, are we learning anything practical and applicable to our own times?

I hope that you, most patient readers, have followed me thus far. Maybe you get in a vague way what I’m trying to say but can’t pin it down. Some of you might suspect that this is merely a nostalgia trip that meanders from one hazy idea to the next. So let me try and summarize the whole nebulous thought in one short paragraph:

War is too important to society to be left only to the professional soldiery. It must be the serious and routine business of the whole citizenry. Let us learn from our rich military legacy, not just through films and books, but by preserving and using what is still of practical use.

###

To be sure, the country has long been implementing a citizens military training program. In the 1960s, our high school military training (then PMT, now CMT), for example, required junior and senior male students to drill on Saturdays. (From the late 1970s onwards, it became a requirement too for female students.) Did that make us capable citizen-soldiers? You bet it didn’t.

We merely trained with mock Springfield bolt-action rifles of World War I vintage – in the era of M16s and AK47s! We were taught parade drill basics, starting with the ABC’s of carrying arms – you know, Kanang balikat, ‘Ta! Handa, ‘Ta! Parangal, ‘Ta! Baba, ‘Ta! Tikas pahinga, ‘Ta! – as if those choreographed skills were more helpful to a young citizen-soldier when war did knock on our doorsteps, rather than learning how to actually load, aim and fire a rifle properly.

###

When I joined the cadet officer candidate corps (COCC) in high school, I half-expected to learn a bit about real weapons and tactics, maybe survival skills in bivouac or on visits to the UP ROTC arsenal, where they kept M1 Garand rifles that actually worked, or so I was told. Instead, we spent hours drilling around the school grounds with airy goose steps, fancy rifle routines, tiger looks and snappy salutes. As cadet officer wannabes, we also learned to brandish chrome-plated sabers bought cheap from a military supply store.

“Oh, I’m sure you loved to twirl your saber, huh, while you strutted on the parade grounds,” Kabsat Kandu ribbed me with his double-edged hinalong wit. “And in front of the adoring girls too!”

Being popular with the girls was a big incentive, I admit. Only, I didn’t get to reap the said benefits, since the School Commandant dropped me from the cadet officers’ roster near the end of our training, because I had joined anti-fascist protests after Marcos suspended the writ of habeas corpus in 1971, fraternized with FTA sloganeers (if you know what I mean), and in the ultimate act of defiance, boycotted the Cadets’ Ball.

###

To be honest, I liked the rigorous training that improved our postures and stamina through plenty of push-ups, squats, and double-time marches around the campus. But I felt I didn’t learn anything that could be of good use in a real war situation.

Many of my classmates felt that our play-soldiering was a waste of time. Campus protests demanded to scrap PMT or replace it with more useful activities. I was reluctant to drop out, but looking back, it was inevitable.

I learned more about first aid and jungle survival in three years of Scouting, than in my entire high school PMT plus a short stint with the UP ROTC. The few arnis routines taught by an uncle gave me a better sense of hand-to-hand combat than the fancy sword moves displayed by cadet officers.

###

If the CMT and ROTC authorities had not allowed us to even just hold real guns, they should have at least trained us in martial arts and survival skills, which go back deep into our nation’s past.

In an Internet interview, Cass Magda, a California-based martial arts teacher and researcher, said he considers Filipino martial arts a most valuable self-defense system. “It is a weapon-based system that evolved uniquely because of the resistance to the Spanish occupation of the Philippines for nearly 400 years.”

It is said that kali, our ancestors’ comprehensive martial arts, was taught to all boys as a course with twelve subjects: olisi (single or double stick, sword, axe), olisi-baraw (long and short sticks, sword and dagger), baraw-baraw (double short sticks, daggers), baraw-kamot (dagger and empty hands), kamot-kamot or pangamut (empty hands), panuntukan (native boxing, which includes the use of elbows), panadiakan or sikaran (kicking, including kneeing and use of the shin), dumog or layug (grappling, wrestling), olisi dalawang kamot (two-handed stick style), sibat or bangkaw (use of spear, staff), tapon-tapon (use of hand-thrown darts and projectiles), and lipad-lipad (use of blowguns, bow and arrow).

Later, Magda says, “elements of Spanish swordsmanship were absorbed and modified to fit [our ancestors’] needs for effective countering attacks and used reciprocally against the Spanish and European invaders.”

###

Magda notes: “Other martial arts have forms that look pretty, but Filipino martial arts have the understanding of how the weapon structure of combat really works. Once the principles of this structure are understood then anything can fit into the structure.”

“You see, the Philippines was a blade culture. In ancient times everyone carried a blade, by the time you were 14 years old you could be wearing a sword. It meant that you were now respected as an adult in the society. You were capable of preserving or taking a life. You had a great responsibility as a preserver and protector of the society. You became the servant of the people of your tribe.”

###

Historians are agreed that our ancestors had a mastery of weapons and warfare skills, and a deeply-rooted tradition of combat mobilization and mass heroism. This military capacity could have equaled those of foreign invaders, had we been more politically united.

It wasn’t any superiority of Spanish swords and cannons that conquered most non-Moro areas of the country, but the successful use of “divide-and-rule” tactics combined with Christian missionary zeal. It wasn’t Krag and Gatling guns that finally defeated the Filipino Revolutionary Army, but the warring and wavering factions that wore down its political-military leadership, which worked in the US’s favor.

###

Sifting through Philippine history textbooks, I am frustrated not to find a well-documented answer to a simple question: What happened to the native weapons of our people after they were subdued by the Spanish colonizers?

There are scattered reports about the conquistadors collecting spears, axes and swords from dead and captured warriors. Were these weapons destroyed, perhaps melted, remolded and forged into musket and cannon barrels and ship fittings? We don’t know exactly.

Repeatedly, though, we read about expeditions into pagan territories launched by handfuls of Spanish troops armed with muskets, lances and artillery, and accompanied by hundreds of “native allies” armed with the usual spears, swords and axes.

###

So my guess is that the confiscated bladed weaponry simply changed hands. The colonizers could not quickly impose a general ban on indigenous weapons – at least during the first two centuries of conquest. While Spain’s control over the major islands remained tenuous, it had to rely on the military strength of “friendly and pacified tribes” led by their respective warrior-datus to augment the small number of its own troops.

In such an environment, even after subjugation, our ancestors would have retained and developed their combat skills, formations, tactics, and training methods.

This is a modest layman’s theory that has to be validated by historical research.

###

I speculate that a major change of Spanish military policy occurred after the British invasion (1762-64), the subsequent near-simultaneous revolts in wide areas of Luzon (e.g. the Palaris, Silang, and Cagayan uprisings), which also saw the height of the Dagohoy revolt and Moro wars. The colonial regime suppressed the private armed groups under the native principalia, cracked down on native weaponry, and relied on direct native recruitment into the colonial infantry and later into the guardia civil.

This would have driven indigenous martial practices underground or into the unpacified territories.

###

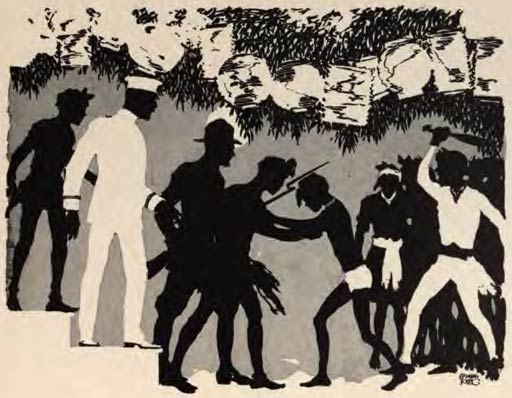

In colonized territories, the prohibition gave rise to ostensively harmless activities that the Spanish authorities allowed or even encouraged. For example, in the popular practice of moro-moro and sinulog, our forefathers preserved at least the most basic martial skills using mock swords and spears, in the guise of perfecting theatrical or ritualized plays.

Others, not content with choreography, practiced real combat skills secretly in nearby caves and mountain lairs, using real kalis and kampilan (which were banned), as well as shorter utility blades such as badang, itak, or bolo (which were allowed as all-purpose tools) and sword-length rattan sticks.

Later on, towards the end of Spanish rule, the various efforts to preserve indigenous martial arts in covert and overt forms gave rise to more sporty, Spanish-influenced martial arts such as arnis de mano (from “harness of hand”), eskrima (from “fencing” or “skirmish”), and baston (from “cane”).

Thus, our native combat skills continued to evolve from father to son, from master to apprentice, from one generation to the next.

###

Although the new American colonial authorities must have frowned on combative forms of kali and arnis, it is said that other forms limited to sticks and empty hands went mainstream in the 1910s after the remaining pockets of anti-US armed resistance were wiped out.

The various regional forms began to blend by the 1920s and 1930s, as landless Luzon and Visayas farmers resettled in Mindanao, and even spread overseas as Filipino migrant workers trooped to farms and canneries in California and Hawaii.

But we are getting much ahead of our story.

###

In the wide uncolonized areas of Mindanao and the Cordillera, the old warrior traditions continued in full throughout the Spanish era, despite (or probably because of) repeated Spanish punitive expeditions into their tribal territories.

Unlike many Native American tribes who became expert horseback gunfighters and thus fought tit-for-tat with the highly mobile US Cavalry, the Moro and Igorot resistance fighters continued to rely on indigenous arms even during the 19th century, when the rifle was already a common weapon that they could have seized in battle or bought from gunrunners. Perhaps they found it unwieldy in a jungle ambush, perhaps they couldn’t solve the problem of replenishing ammunition; further research is needed on this.

At any rate, they too were eventually marginalized. US imperialist troops, after defeating the main contingents of the Filipino revolutionary army at the start of the 20th century, proceeded to conquer the Moro, Igorot, and other peoples. The ban on indigenous weapons became more thorough and strict. Confiscated swords, spears, daggers and axes eventually turned up in public museums and private collections.

###

But the native warriors fought hard, and died hard. Whether it was a matter of indigenous preference or simply due to lack of firearms and bullets, Moro warriors and other native fighters adopted do-or-die tactics that unnerved Spanish troops and later US troops. There was, for example, the legendary sword assault by suicide warriors, variously known as juramentados, pulahans, or tadtads.

Suicide volunteers had their limbs and torsos tightly bound in fibrous cloth or leather strips. Then, on signal, they assaulted the enemy lines with kampilan, kalis or bolo tied with thongs to the wrist of each hand, as they shouted “Allah’u akbar!” or “Mabuhay ang Pilipinas!” or simply “Tadtad!”

The wrappings would not stop a hail of Krag bullets, but they deadened the impact and slowed down blood flow. This enabled most attackers to reach enemy lines, perhaps mortally wounded but still with enough strength to take a dozen or so unfortunate souls with them on the way to martyrs’ heaven.

###

Such suicide attacks struck terror in the hearts of the bravest American soldiers. That is, until some wise guy inventor named Samuel Colt invented a magazine-loading semi-auto pistol called the Colt caliber 45. The Colt .45 had tremendous stopping power exceeded only by machine guns of that same period, and which proved crucial in close-quarters combat.

Modern automatic firearms eventually decimated the kalis-wielding juramentado rebels. But they did not kill the Filipino faith in the native sword. As late as World War II, the armed strength of guerrilla units in Northern Luzon were doubled or tripled by so-called bolo battalions, even if much of their work was limited to defensive works, intelligence, and logistics.

The last Filipino samurais went down to their glorious deaths when the Lapiang Malaya quasi-religious rebels were mowed down with M16 automatic fire by Metrocom troopers at the Manila-Pasay boundary on Taft Avenue in 1967. After the LM massacre, the next generation of rebels throughout the land decided to finally retire their swords and fight back with their own M16s, AK47s and FALs. (Read Dennis Villegas’ “You shall be as gods: the enigma of anting-anting” for a detailed account of the Lapiang Malaya massacre.)

###

“Oh no, no, no, please! Don’t write off Filipino martial arts just yet,” blurted Kabsat Kandu. “We arnis enthusiasts will yet have a role to play in the next revolt.” Hmm. Sometimes my pesky friend has some interesting notions up his sleeve.

True, we are now on the verge of another People Power revolt, and most analysts say it won’t succeed unless backed by the AFP and PNP. I say, our people should not wait for the AFP and PNP to move.

If war is too important to society to be left to the professional soldiery, then more so in the case of politics – especially People Power politics. I say, our people should be out there in the streets in their hundreds of thousands and millions to oust an illegitimate regime.

“I say, it’s time for Oust-GMA rallyists to fit their placards and streamers with sturdy rattan and bamboo handles,” Kabsat Kandu exclaimed.

“Is that an appeal to arms?” I asked.

“You bet it is,” he glowered. #

You sound like a spambot, but I’ll give you the benefit of the doubt. Permission granted.