Author’s note: This was first published on 18 May 2003 under my Pathless Travels column published by Northern Dispatch (Nordis) Weekly. I’m reposting it here in three parts, with some revisions to update my own understanding of the issue, and to make it more timely. Read Part 2 here.

After a couple of false starts, I guess we can now safely welcome the onset of that relentless stretch of scorching days we call “Philippine summer.” You know, school’s out, need to beat the heat, so everyone and their dog head to the beaches or to the mountains.

Invariably, planning one’s summer itinerary soon leads to more talk about the coming rains and one’s school plans at the end of the so-called “Philippine summer.” Invariably, too, the changing of the seasons also revives the long-standing suggestion of changing the Philippine school calendar so that classes start in September instead of June.

The usual argument is that, supposedly, the rainy season is at its heaviest —and thus most disruptive of classes — during the months of June, July and August. Hence the presumed advantage of starting the school year in September.

The other side of the debate objects to the idea, realizing that the proposal will turn April, May and June into school months. “You policy freaks are so killjoy. Get a life! Summer is for kids, so let them enjoy it without worrying about classes,” they will argue. The presumption, of course, is that there’s an unchanging, non-negotiable Pinoy summer.

This policy debate may seem minor, but it will continue to simmer until everyone agrees on the pros and cons and their relative weights. There are pros and cons for starting the school year in June, or September, or any other month for that matter. One suspects that the biggest argument in favor of a September school opening is that we will then be synchronized with the school calendars of most schools in the United States and Europe — the favorite destinations of the children of Filipino elite. Or perhaps the reverse is also true — the synchronization makes it easier for foreign students to enroll in Philippine schools, whatever their reasons for studying here might be.

Personally, I rather like the simple symmetry of a school year that starts in January, with month-long breaks in June and December. Australia and New Zealand follow this kind of school year. Coinciding with the calendar year and the fiscal year has some practical advantages, too, even if that might entail drastic changes in the rest of the entire Filipino calendar.

For one thing: If the school year starts in January, maybe people would think more about saving up their 13th month pay or Christmas bonus for January’s enrollment expenses, instead of splurging it all in the usual December frenzy of consumerist hedonism. But that’s for another column piece.

At any rate, let the school-calendar debate simmer longer.

Mythical Philippine summer

My gripe for now is that both sides of the debate generally accept the wrong notion that the “Pinoy rainy season is at its heaviest” in June, July and August. The corollary presumption is that there is a “Pinoy summer” that inevitably falls around March, April and May, and that it’s exceedingly enjoyable for kids because it’s, well, summer. You know, lots of sunshine, riverside picnics, fun on the beaches, colorful fiestas and long afternoon siestas.

This mythical Philippine calendar, perpetuated by some mindless media tradition and school textbooks, isn’t very accurate for at least three reasons.

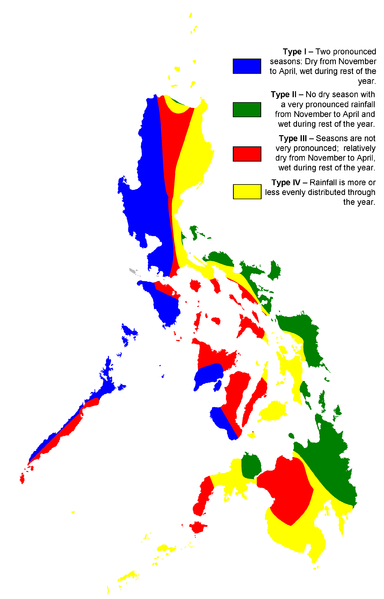

First, not all parts of the country are affected equally and at the same time by the southwest monsoon, the arrival of which typically signals the onset of the rainy season in those parts of the country that experience a marked dry season. Which also means there are portions of the country that don’t experience a distinct dry season or “summer.”

There’s the northeast monsoon, too, which also brings some rains in other parts of the country at other months of the year, but is less popular in the public mind.

Second, not all parts of the country lie within the typhoon belt, which is a major factor in marking the extremes of rainfall and destructive winds. Mindanao for example is largely outside the typhoon belt.

Finally, late-season typhoons arriving in August, September and October, while less frequent, tend to be more power-packed. So, there goes Pfft! your perfect September opening of classes.

Variations in rainfall patterns

PAGASA operates a number of rainfall-measuring stations throughout the country. A full set of monthly and annual rainfall statistics from at least eight stations (Laoag, Dagupan, Manila, Legazpi, Iloilo, Cebu, Zamboanga and Davao) are published in government yearbooks.

(Author’s note: An undated PAGASA report, “Operational Agrometereological Services in the Philippines” by Adia Jose, Flaviana Hilario and Nathaniel Cruz lists 60 synoptic weather stations that it maintains throughout the country, while another undated PAGASA report presented by Thelma B. Acebes says there are 210 stations that measure and record daily rain data. These data, accumulated for at least half a century, are supposedly compiled by PAGASA into database format although it’s not clear how the public can access them.)

One would expect that every mass media office or library would have at least a set of these statistical yearbooks, and thus help us straighten this myth about the “Philippine rainy season” and the “Philippine summer” that supposedly precedes it throughout the archipelago.

Indeed, if we study the rainfall patterns in various regions of the country, we will realize that there is a widely fluctuating range of monthly — not to mention weekly and daily — variations in rainfall averages, as we go from north to south and more markedly from west to east. (Let’s not even consider the yearly fluctuations due to the El Niño-La Niña cycle.)

The different rainfall patterns for the eight listed PAGASA stations are evident at first glance.

Laoag, Dagupan and Manila exhibit that classic Western Luzon rainy season peak that comes around June, July and August. In these areas, the dry season usually starts around October or November, and gradually intensifies until it peaks around March or April, aggravated by very warm air temperatures.

This annual rainfall pattern is what is usually mistaken as a country-wide phenomenon. Thus the myth of a “Pinoy rainy season” and “Pinoy summer.”

On the other hand, the Legazpi and Davao PAGASA stations report a very different picture of annual variations, in that rainfall is more common throughout the year, and thus these areas experience no distinct dry seasons although there could be seasonal peaks in rainfall.

These climate types are representative of the Pacific-side areas of the country such as the Sierra Madre belt, Bicol, Eastern Visayas, and eastern and southern Mindanao.

Indeed, if one is obliged at all to identify a peak season of rain for these Pacific-side areas, that would be from November to March, although rainy weather could just as easily occur anytime throughout the year. This is often what is interpreted in the Manila-based (and usually Manila-centric) mass media as “off-season” rains.

Alongside these two rainfall extremes of the western and eastern sides of the country, we can delineate two other intermediate or transitional belts.#

Author’s end note for Part 1: I wrote this column piece in 2003, when resources on Philippine climate zones were not that accessible on the Internet, and when my own Internet access was too slow to make much use of online databases.

These days, however, I suppose it would be much easier to check Philippine rainfall patterns measured at various stations by simply going to such sites as the IRI Data Library for records on historical precipitation, or by sending a researcher to the PAGASA office, armed with a USB flash drive. But that’s just me supposing. I know for a fact that when I was with a GMA News Online team working on an interactive El Niño map, a team member assigned to get the map data from PAGASA had to go through some bureaucratic red tape before she could get all the information we needed.

PAGASA now explains that the most clearcut indicator signalling the start of “Philippine summer” is when the annual northeast monsoon ends. This year, for example, PAGASA officially declared the official start of summer last March 3, which it did not reverse despite the series of rainy days in Metro Manila that followed its announcement. The weather bureau is also expected to declare the end of summer at the onset of the southwest monsoon — even though this other monsoon affects various parts of the country in different ways.

PAGASA also claims that “the Philippines’ hottest months are April to May,” with a mean temperature of 28°C in May, while its “coolest months are from December to February,” with a mean temperature of 25°C in January. That may be so in terms of national averages. But a closer look at the monthly temperature means for selected cities will show that the range of daily highs and lows is much broader than seasonal differences: 23°C-31°C in May and 22°C-30°C in December in Borongan, for example; 25°C-31°C in May and 24°C-31°C in December in General Santos, as another example. Thus, seasonal temperature differences are also not a very good measure for defining that elusive notion of “Philippine summer.”

So I guess I will just have to explain that there’s more to the Philippine climate variations than meets the eye. Or the skin, as it were. Onward to Part 2, then.

If September is the start of school year, students will be safe during rainy seasons and they don’t have to worry if there’s a class or none. They don’t need to study and instead have a rest during this seasons. But during January-May, there’s also a lot of fiesta and traditions Filipino’s are celebrating

But Leah, this is precisely my point: that the rainy season is unevenly distributed in various parts of the archipelago. Just consider this: Ondoy, Pepeng, Pablo, Sendong and Yolanda all happened during the September-November period.