Those who stayed for extended periods in the old Kamuning house invariably noticed the books. Four tall book cabinets higher than a grown man (two in the living room, two upstairs), and additional bookshelves scattered all around the house, contained hundreds of titles, when we young siblings still lived together with our parents under one roof.

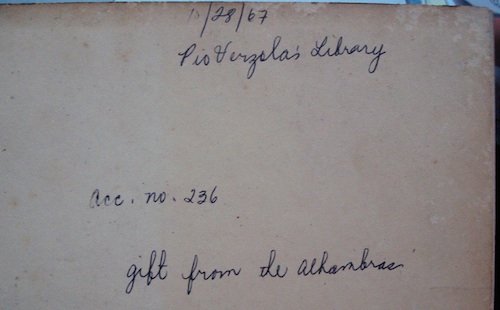

This huge assortment of books, pamphlets, monographs, and a Britannica set (1968 edition) even had a name: our parents called it the “Pio Verzola Library” and had the most important volumes stamped and tracked with a card pocket at the back of each book. My mother had some library training, and so we kids were taught that the books at home followed a system similar to what we followed in the school library.

Later, when one by one the four of us set up our own households, each one took a sizeable number of volumes from this ancestor library and combined it with his or her own collection, gradually accumulating decades of book love (or should I say obsessive-compulsive attachment to books). Thus the old family library replicated into four libraries, stamped with the individual personalities, interests, and historical bric-a-brac of three brothers and a sister.

However, anyone familiar with the old library and browsing through it would inevitably notice one curious recurrence — a number of books would have this handwritten note, together with a date, in addition to the rubber-stamped “Pio Verzola Library”:

Many accession numbers dated in 1967 and 1968 had this or some other variant note: Gift by the Alhambras, Best wishes from the Alhambras, From the Alhambras. So who were the Alhambras? Was our family descended from them or somehow related to them, and was our parents’ rich book legacy a measure of their filial love? Or did our parents perhaps carry an dirty secret, a pathological longing for books, that they ransacked libraries up and down the coast and gathered their loot in Kamuning, where they laundered the evil deed by creating a fictitious wealthy book donor named Alhambra? Does the saying, “Behind every great fortune lies a great crime” apply to this modest private library? After a 45-year mystery, I think it’s time to give the truth its proper due.

The Alhambras were an ordinary middle-class family like us, who happened to be friendly neighbors, with their modest house just a few gates down the street. Mr. Alhambra, if I remember correctly, was in the book-selling business, and I suppose (in my young mind) that he was so successful in the business that his house was flooded with books, his wife and kids up to their neck if not actually drowning in books, and so he could easily give away extra copies to appreciative neighbors.

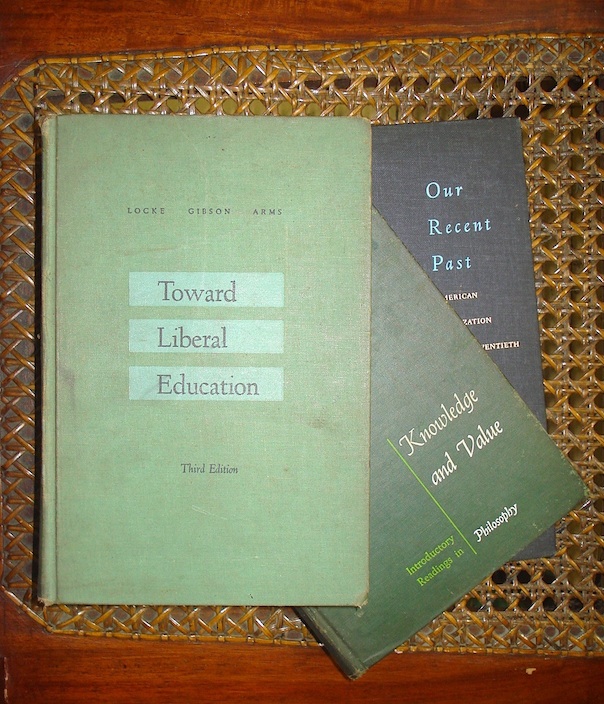

And that is how my parents became friends with the Alhambras. Soon, all kinds of books — hardbound college and high school textbooks (mostly U.S. but not of the USAID “handshake” kind), high-quality paperbound literary classics, and an assortment of other non-fiction titles — started arriving at the house, parcel by parcel. I was too young to understand the psychology and etiquette of neighborly book-giving at such massive scales, so I didn’t bother to ask my parents why, whether they reciprocated the Alhambras, and in what manner.

For me, the issue was simple enough. The Alhambras were nothing less than angels come down from heaven, better than Santa Claus at Christmas. Their gift of books — it must have totaled two or more huge boxes over a couple of years — were a treasure trove of titles, some of which wouldn’t be easily found even in the university library or the high-end hardbound sections of local bookstores. This 11-year-old kid didn’t even bother to thank them, but drowned himself in the books. Just to give you a few examples of what I have: Report of the President’s Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, an 888-page hardbound treatise. The Complete Book of 20th Century Music, 527pp. The Leatherstocking novels by James Fenimore Cooper, paperbound. Mankind in the Making (an Introduction to Physical Anthropology), 351pp. I have to check with my brothers and sister which Alhambra books are in their care.

Truth to tell, my near-psychopathic obsession with books started at a much earlier age. Long before the Alhambras entered the scene, an equally obsessed mother taught me how to read, showed me how to take care of books and magazines, and brought me along on her book-hunting trips at the old PECO building in Quiapo. I now humbly admit to sharing her compulsions, made much worse by today’s easy access to cheaper books. The syndrome is partly physical, triggered by the fresh scents of newly minted books as well as the musty odors of books mottled brown with age. But it is mostly a cerebral and emotional impulse, driven like a perennial urge to discover new friends who bring original and challenging ideas, or like regularly meeting up and renewing old ties with long-standing friends who continue to surprise us with incredibly charming stories.

The episode with the Alhambras helped solidify my bookworm habit into a life-long addiction. Of course that alone did not and could not shape what I am today. My social theory and practice goes way beyond the titles that comprise my current library. But what made the noble Alhambra gesture resonate in me through these years is that it left not just faded memories of a childhood fascination, not just token memorabilia of a family friendship displayed on the top shelf, but a virtual keystone to a hidden architecture that could well outlast the next generations. Sharing it to you now is my way of thanking the Alhambra family.

What this family gave ours were ordinary books, now worn and brittle with age, on mundane topics. But they will continue to speak directly to our family and its younger generations and to remind all of us about a impulse, as deeply felt as when the Altamira cave dwellers beheld the scenes and stories of the hunt, finger-painted by their ancestors and lit only by the flickering fire of the communal hearth. Our own inherited books give us a glimpse of the same deep feeling, which must have impelled the ancient librarians and archivists of Alexandria and Constantinople, of Pergamum and the Roman Forum, of Q’umran ascetics and Han dynastic scholars, to collect the written and printed words of the ages that told of both the wisdom and the follies of their elders, wrought in stone and clay tablets, silk and papyrus, parchment and leather, despite the gnawing knowledge that these puny carriers of human thought and speech will in time crumble into dust.

Civilizations such as ours have this practice of choosing artifacts that most represent today’s lifeways, then putting them into time capsules and foundation stones — to be buried deep underneath buildings or to be sent deep into space. Future generations or alien civilizations might hopefully retrieve them, and so give them a glimpse of how and why we lived at all.

Sometimes the best time capsule or stone foundation is the simplest — books. Collect them, read them, keep them as a library, pass them on to your children to read and care for and build on. Or, better yet, be an Alhambra and outlive yourself. Give out books to people who cherish them. You can’t fail.#Follow @junverzola