Sa ikauunlad ng bayan, bisikleta ang kailangan.—Ariel Ureta, popular radio-TV host in the 1970s

Ariel Ureta, forever associated with this motto under martial law, probably meant it as a harmless play or at most a subtle dig on the Marcos propaganda slogan, “Sa ikauunlad ng bayan, disiplina ang kailangan.” Rumors flew that Ariel was later called to Camp Crame and given a mild dose of Marcosian discipline by being made to bike around the camp for hours—a mere urban legend, as he himself recently clarified.

I was an activist in prison at that time, and didn’t think Ariel had intended to fight the Marcos regime armed with only—of all things—a bicycle. But it was a period of intense crisis, with people lining up for gas and rice as they chafed at the regime’s harsh disciplinarian measures. Ariel wasn’t a working-class hero by any measure. But his bisikleta message must have resonated with layers of deeper democratic meaning among the people.

It also made me miss my younger biking days.

###

Bikes and biking have deep roots in my childhood. We siblings started with the usual toddler trike, followed by a kid’s trolley, then quickly graduated to adult-size bikes. Back then, my hero was a kid down the street who earned an extra peso delivering newspapers by tossing them to people’s yards while on a bike. I wanted to do the same, but I didn’t have a bike, and in any case I was deemed too young (at age 7) to even attempt to ride one. So I had my mother allow me to do a few rounds of newspaper delivery by foot, just for the experience.

Two summers later, my biking hero-worship shifted to other neighborhood kids teaching themselves to ride an adult-size borrowed bike. They suffered crashes and gashes on the legs and arms in the morning, and by late afternoon learned enough to ride proudly around the neighborhood. And that, too, was how my brothers and I learned.

We had a shiny new red-and-chrome, fixed-gear (single-speed), generic-brand bike—the standard size used by adults. We didn’t know about wheel stabilizers and knee-pads and helmets. So we just went for it and learned to ride anyway, crashes and all. By summer’s end, our bike had become dilapidated, creaky and dented every which way but loose. But it was ours, and we used it ruthlessly.

###

During those same years, I rarely saw a racing bike in our lower-middle class neighborhood. But there was one unfailing time and place when practically the entire neighborhood (or at least most of the men and us kids) watched a dazzling array of racers whiz by. It was around May, the most exciting part of summer at any rate, when the two-week Tour of Luzon came to town.

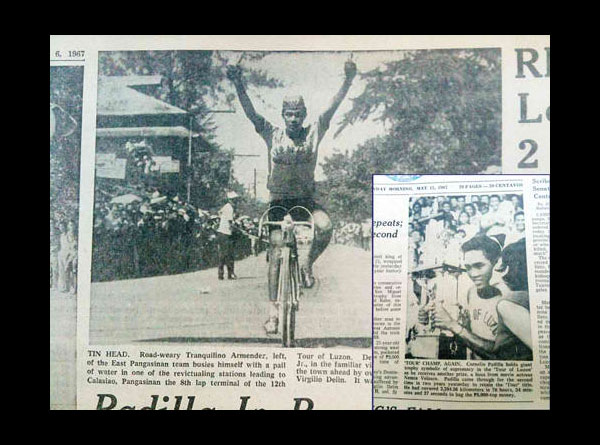

The Manila Times, which was the race’s main sponsor, ensured full media coverage. We followed every lap on DZMT, with crisp field reports annotated by the loquacious commentaries of Joe Cantada (he with the perfect English) and Ronnie Nathanielsz (he with the weird accent). The overall standings and lap results were also graphically presented, as an early example of effective data visualization, on the Times’ front and sports pages.

The final lap, often the most dramatic, ran across Central Luzon through the MacArthur Highway, turned east at the Bonifacio Monument, wheeled through nearly the whole length of Highway 54 (now EDSA) until it turned west (at Buendia I think), all the way to the Rizal Memorial Stadium for a rousing finish.

We joined the crowds of people along the highway, craning our necks as the convoy of Tour team vehicles and police escorts cleared the route. Many of us had small transistor radios glued to our ears, keeping track of the lead pack’s composition and whereabouts so we can jostle for the best view and spot our favorites as they sped by. We reserved our most robust yells for the ace riders who wore the yellow and green jerseys.

I will never forget the rush of adrenaline as we watched the cyclists amid the roaring crowd and the screaming sirens. They were certainly not glamorous actors in designer shirts posing on floats at a film festival parade. Rather, they were sun-bronzed warriors on pedals, wearing team colors often muddied and bloodied by road spills, bathed in profuse sweat and pailfuls of water thrown by the crowd, and scrambling for every split-second road advantage.

###

They were the working-class heroes of my generation—of the biker kind, I hasten to add. They filled up our imagination for weeks. I wanted to be like them.

The Tour of Luzon produced the legendary Cornelio Padilla Jr., a newspaper delivery boy in Project 4 who at 17 won an amateur national cycling event and represented the Philippines in the Tokyo Olympics, and then went on to win the Tour of Luzon back-to-back in 1966 and 1967. He used his earnings to finish law, then served as legal consultant and later top executive of the National Book Store. Some sports writers think he was the greatest Filipino cyclist ever.

The Tour of Luzon (and its successor events) produced other cycling greats who came from lower social classes, like Jose Sumalde of Bicol and Jess Garcia Jr. of the fabled West Pangasinan team. Other champions included Antonio Arzala, a former cemetery caretaker and newspaper boy; Reynaldo Dequito, a cigarette and fishball vendor; and Paquito Rivas, a pedicab driver. The backgrounds of 1960s-70s cycling greats like Mamerto Eden, Rodrigo Abaquita, Jose Moring, Domingo Quilban, and Maui Reynante should also be worth researching and retelling, as their stories are now alien to younger generations.

###

Sadly, those days are gone. In the tumultuous years of 1970-72, the Tour of Luzon was canceled and the Manila Times (its main sponsor) shut down. When the Tour resumed in 1973 and plodded through the next decades under various corporate sponsorships, much of the old working-class spirit gradually faded away.

Jess Garcia himself, writing for the Dagupan Sunday Punch, noted that the Filipino sports cycling community had become a shadow of its old self.

Philippine sports heroes are now produced in very different ways, shackled to high levels of corporate sponsorship, sports technology and foreign connections, which require hefty and sustained funding. We still have sports icons that the masa can identify with, but how many are they, and how did they get to where they are now? How many can hope to be the next Manny Pacquiao or Efren “Bata” Reyes?

One would think that more young Filipinos today would dream of becoming cycling champions and competing in world-class cycling competitions. After all, cycling is a very socially productive sports activity—not like boxing where you are oddly rewarded for beating your opponent, quite literally, with your fists. Cycling in the Philippines has a potentially huge mass base of enthusiasts, which could eventually grow to be as big as or bigger than that of basketball. After all, the country has more roads than basketball courts.

But major obstacles remain. Here I will only briefly mention three big ones.

First, acquiring or building a bike remains costly. The trend is towards more affordable bikes, with the cheapest brand-new ones now in the P5,000-10,000 range. But this is only due to cheap imports from China and Taiwan, which may be transitory. Bike rental facilities are miserably undeveloped, and the risks of having your bike stolen are a definite disincentive.

Second, there aren’t enough bike lanes and support facilities in the urban areas (including ovals and parking racks) for riders to use safely and conveniently. At best, protected bike lanes are too few, narrow and fragmented, with no safe crossings through main thoroughfares. Thus, there is as yet no critical mass of daily street bike users that can make a difference.

Third, and closely related to the first two, biking has no place in the government policy and planning milieu except in a handful of localities. There is no program to develop the local bicycle-making industry for the domestic market. There is no integrated traffic system that supports and protects bicycle users. (More on these in another blog piece.) The biggest road concern is still disiplina ang kailangan, not bisikleta ang kailangan.

###

I could mention more. But let me end with one simple point:

Philippine boxing has Pacquiao, Donaire et al. to fire up mass enthusiasm in the realm of popular culture and our collective psyche. Philippine basketball and (more recently) football have a slew of collegiate and post-collegiate stars, sleekly packaged by advertisers, to do the same. But where are the Filipino biking greats to show us the way to cycling glory?

Where is our version of the Amsterdammers during the Nazi occupation, who in their tens of thousands resisted every effort by German authorities to confiscate their beloved Oma bikes, and who turned these instead into actual tools of the Resistance? Where is our version of the Dutch Provo activists, who introduced the White Bicycle as their tool for anti-capitalist rebellion in the 1960s?

Where, oh where, are our working-class heroes of the biking kind? Please show up soon. #