One common Northern Luzon artifact that has always left me with many unanswered questions is gongs – gansa or gangsa in most Philippine languages (ultimately from Sanskrit kamsa or kansya “bell metal”).

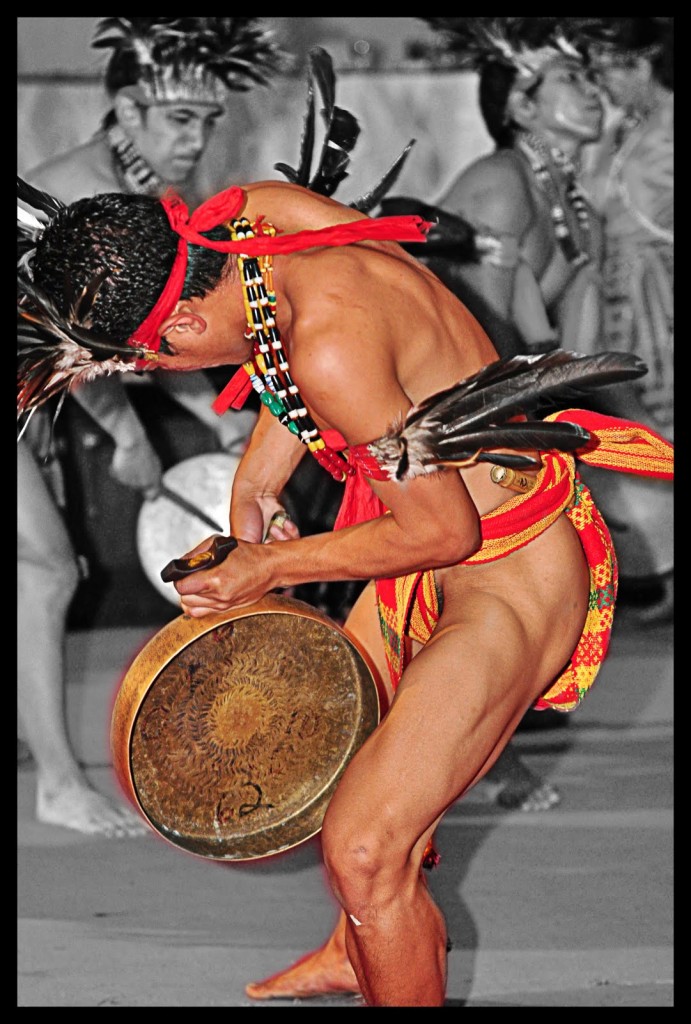

How gongs are played and used in Cordillera dances was the topic of a very informative article prepared by the cultural alliance Dap-ayan ti Kultura iti Kordilyera (DKK), which was serially published in Nordis in 2001.

The role of gongs in Philippine prehistory was covered, although in rather sketchy glimpses, by W.H. Scott in his various works. I lightly touched on that topic in this column in 2002, as I attempted to explained why the Nordis masthead includes a gangsa.

But one big blank wall remains this: Where did our indigenous communities get their gongs, and ultimately, where and how were these gongs made?

###

Good leads were provided by friends in the DKK and Bibaknets (an email list of Filipinos with Cordillera origins). They pointed to some Mankayan craftsmen and their families who are capable of turning out brass gongs, selling these at P10,000 per set [at 2003 prices]. The craft of producing the so-called “Nilepanto” (Lepanto-made or Lepanto-style) gongs is being passed on from father to son, and promises to continue into the future as it is becoming lucrative business.

But this indigenous capacity to make our own gongs, it appears, is a fairly recent development. In an article on the metallurgy of gongs co-written by Harold Conklin for Archeomaterials, he noted that among Cordillera indigenous peoples, there are strongly-rooted indigenous traditions of iron forging and of “lost wax” casting of precious and cupreous metal decor, but none of making gongs.

I combed through various books on Philippine prehistory and ethnographies written during early Spanish contact, but couldn’t find any concrete evidence about pre-Spanish Filipinos being able to manufacture their own gongs. Instead, we seem to have depended mostly on outside sources of gongs, which we obtained through trade.

And when we talk of ancient, or heirloom gongs, what we actually mean are the bronze gongs, not the Nilepanto brass gongs. The greatly-valued bronze gongs are more durable, sound more resonant, and are thus the preferred lead instruments in gong ensembles. Such heirloom gongs are reported to have survived intact in some communities for more than seven generations, despite frequent and vigorous use.

Bronze gongs are of course a lot more expensive. They are reported to be from 10 to 25 times more valuable than brass trade gongs. In fact, in the whole Cordillera, bronze gongs are considered as the most valued of all traditional musical instruments and are ranked among a clan’s most cherished heirlooms.

###

Why is this so? Is it just because bronze gongs happen to sound better, or is there some mysterious magic at work here?

At this point, I can’t avoid but go into the ABC’s of metallurgy since we are discussing how gongs are made. The key point is to differentiate between brass and bronze.

Brass is an alloy of 60-67 percent copper and 33-40 percent zinc, and often has substantial amounts of lead. Working with brass usually involves only casting (pouring molten metal into molds to solidify into useful shapes) and cold-working (hammering brass pieces into shape without heating). The presence of lead is needed to increase the alloy’s fluidity in casting. Brass gongs must have been cast, then simply hammered to final form.

Bronze, on the other hand, is an alloy of copper and tin. Artifacts from Bronze Age diggings varied in proportion from 67 to 95 percent copper. Bell metal, a type of bronze alloy that produces a sonorous sound when struck, has a high tin content: from one part in seven (about 14 percent) to one part in four (25 percent).

Now here is the interesting part: The type of copper-tin alloy that goes into the making of bronze gongs is not just defined by a strict proportion (22-24 percent tin, no traces of lead), but more importantly in how the alloy is produced and treated in the workshop.

The process of making bronze gongs is much more complicated than that of brass gongs. It involves repeated alternations of hot forging (hammering bronze pieces while red-hot) and quenching (dipping the pieces into cold water in between hammerings, to make them more ductile and malleable).

###

Archeological records show that this type of alloy (bell metal) was already widely used in the past two millennia in China and Southeast Asia. A few artifacts from the Middle East and India – such as a small bowl from Iran made of a similar alloy, dated to about 1000 B.C. – suggests that the production technique may have spread to this part of Asia long before the Christian era.

Along with porcelain and stoneware jars, bronze gongs have served Southeast Asian societies in the past millennia as culturally valued trade wares, providing their owners not just with fine implements for music and dance, but also powerful symbols of high status that could be passed from one generation to the next.

As bronze and brass gongs spread to the archipelagos of Southeast Asia, two major forms emerged. One was the bossed form, with large and small bulges on the gong’s surface. The other was the flat form, where the gong was a simple flat surface with its rim bent to form a shallow drum-like cylinder. In Northern Luzon, only unbossed, flat gongs are known.

###

So what’s the point in discussing all this?

Well, because it turns out that in the past centuries, and probably until now, indigenous communities in Northern Luzon—perhaps even in other parts of the country—have never really developed the local capacity to manufacture gongs made of this bronze alloy (bell metal). As far as could be traced by archeologists and researchers of present-day artifacts, all bronze gongs used in the Cordillera are of foreign – presumably southern Chinese or mainland Southeast Asian – origin.

As Prof. Conklin related, experienced Ifugao traders in valuable artifacts revealed that their sources of bronze gongs go back to pre-World War II Chinese merchants at the mouths of the Cagayan, Abra, and Amburayan rivers on the northernmost and northwestern coasts of Luzon, respectively.

This point is most significant, because it now appears that all Cordillera heirloom bronze gongs still in existence were made in China or Indochina at least more than 60 years ago, perhaps more than 150 years ago. Luckily for us, Prof. Conklin’s study included the most complete description accessible to us of traditional gong making in China during that time: an 1869 account by Paul Champion.

Champion described Chinese gong manufacture in fine detail, only a summary of which could be listed here:

###

Melting

Merchants gather pieces of broken gongs. Metal for new gongs are produced from broken-gong scrap, never from virgin copper-tin alloy. The pieces of scrap metal are heated in a furnace until they become dull red, then cooled. The cooling metal becomes brittle, and is broken up into still smaller pieces. The purest pieces are chosen, put into a refractory clay crucible, then reheated and melted down in the furnace.

Casting and initial forging

The melted metal is poured out into a mold – an iron disc on a stone support, surrounded by a thick rim of clay formed like a doughnut and covered with a conical cap of fired clay. The molten metal is poured through a hole fitted with a funnel in the center of the cap.

When the metal solidifies, the clay cap and rim are removed. The red-hot metal blank, now a disk 1 cm thick, is subjected to a first forging on a high anvil using a roundhead hammer hafted to a long, flexible cane of bamboo.

Main forging

The piece of metal, given a curved shape in the initial forging, is reheated to a dull red color and placed on the anvil for the main forging.

Four or five workers give rapid blows with long iron hammers, while the foreman adjusts the piece with iron tongs to ensure an even forge. Three of the workers strike successively, with all their strength but with precision. The two others beat in turn with heavier hammers.

As described by Paul Champion: “This forging operation is truly fascinating, one cannot avoid admiring the skill, the precision of these smiths, who beat, four or five of them, a piece of small size and who manage very heavy and bulky hammers without ever getting in each other’s way.”

When the piece has cooled somewhat, it is reheated and forged again until the gong has almost attained its final dimensions.

Stack forging

Next, five or six gongs being worked are stacked on top of one another, reheated, then hammered together on the anvil using both long iron hammers and wooden mallets with flat faces. This beating could last up to an hour, for 50-cm gongs.

Trimming, quenching, and salting

Then the pieces are taken apart and worked separately.

The piece’s edges are trimmed with a pair of shears, and the rim is given the desired shape with iron hammers or wooden mallets. Next, the piece is reheated to a dull red, then immersed for 5-6 seconds into a large barrel of cold water.

Then the still-hot gong is rubbed with a cloth wad soaked in salt water. The water evaporates, leaving a thin coat of salt. The gong is again taken to the fire, turned in every direction, then hammered once more.

Bending and more tempering

The gong is subjected to further heating and hammering to bend its edges. This requires skill and precision, and the slightest wrong blow could crack the metal. The piece is reheated again to a dull red, quenched again in cold water for 2-3 minutes, then hammered again with a wooden mallet.

Finishing

The piece is then worked with two short hammers, with one of them beating one side and the other serving as an anvil on the other side. Then the piece is hammered again using a special technique involving vigorous but short and tightly controlled blows.

Finished gongs generally show the marks of this last hammering. Sometimes it happens that the gong breaks while being beaten in this last phase. (Broken gongs are scrapped.) The last step consists of cleaning and scraping the finished gongs with steel tools.

###

Apparently, the Chinese quenching and hot-forging technique was a fine art that has not yet been duplicated by modern Western metallurgy (although a scholarly paper on two cymbal makers in North America seem to indicate otherwise). Too little or too much, too early and too late, spelled the difference between a durable and sonorous bronze gong that remained intact for many generations, and one that easily cracked and produced a tunog-lata (thin, tinny) sound, especially when struck too forcefully.

I hope an Igorot metallurgical engineer reads this and becomes fired enough to reproduce the traditional Chinese gong-making technique locally. We have the skilled manpower, the knowledge of indigenous furnace technology, and rich supplies of copper (gambang), while the tin supply is easily solved. Let us make our own bronze gongs! Then, and only then, could we really claim Cordillera gongs as indigenous in its fullest sense. #

Author’s note: This article was first published in the Northern Dispatch (Nordis) Weekly on 7 December 2003. It is reposted here with minor revisions.

Hi Martin–

I was cleaning up tons of spam on my site when I stumbled on this one of a few authentic and interesting responses. I forwarded it to my son, who is an Asian Ethnomusic major and whose forthcoming thesis is precisely about Northern Luzon indigenous music. Thanks for the link and pingback!

–Jun