Today is March 29, and a Good Friday as well. Notice any curious coincidence?

The first is the anniversary date of the New People’s Army—the Communist-led rebel armed force that has been the present Philippine state’s continuing specter since it was established 44 years ago, in Tarlac province.

The second is of course the traditionally observed day (which changes from year to year) of Jesus’ crucifixion and death—a multiple irony since a peace-loving prophet who claimed he was the Son of God was arrested for “declaring himself King of the Jews” and was executed in the most excruciatingly painful manner practiced by the Roman authorities.

One date is celebrated with joy by Communists and the rebel forces they lead in a small Asian country; another day is observed annually by the world of Christendom, often with somber or even morbid rituals. Could we think of a more extreme clash of images occurring on the same red-letter day?

Well, the contrast only appears extreme because we’ve always been taught that Jesus consistently preached and practiced peace and love for one’s enemies, while the NPA untiringly pursues a “people’s war” to overthrow the current reactionary state.

But is it really that extreme? There are subtle commonalities. Palestine is also a small country in the opposite side of Asia, and has long been wracked by colonial conquests and anti-colonial armed struggles. In fact, some scholars who have delved into the records of ancient Palestine believe that some 2,000 years ago, the “historical Jesus” actually led, or at least represented, a revolutionary mass movement that called for (and eventually resulted in) an armed struggle to overthrow Roman colonial rule and its local puppet tyrants.

I particularly liked a series of essays by cultural anthropologist Marvin Harris that were later compiled into a book, Cows, Pigs, Wars and Witches: The Riddles of Culture (1975, London: Hutchinson & Co).

In two chapters of this excellent book, Dr. Harris explained the roots of military messianism in biblical Palestine (in the chapter “Messiahs,” pp. 155-175) and how much of the primary if fragmentary evidence led him to conclude that Jesus, his disciples, and their mass movement fought for a concrete political platform even if couched in religious terminology (in the chapter “The Secret of the Prince of Peace,” pp. 179-203).

Here are the most crucial of Dr. Harris’ arguments (mostly in his words, which I merely paraphrase) in favor of the historical Jesus as a military messiah, an armed revolutionary—and not the Prince of Peace, as the Church founded in his name has preached in the past 2,000 years:

The Jesus-David connection. Jesus traced his roots and modeled himself after David, the founder of the first and largest Jewish empire. Jesus’ followers called him messiah (originally meant, probably, any person possessing “great holiness and sacred power”) and the Anointed One (who would rule in partnership with Yahweh). David, in his own time, was also seen and called in the same terms by the Jewish people.

Yahweh’s promise unmet. David, born in Bethlehem, rose to power from humble beginnings. As a leader of a guerrilla movement, he won victories against insuperable odds. Yahweh made a covenant with King David that his dynasty would never end and would “rule over many nations.” But once David died, his empire began to crumble and the Jewish people were almost continually downtrodden by imperial armies of ancient Asia, Africa and Europe marching against each other, down to Jesus’ time.

The need for a military messiah.The Jewish theocracy explained that Yahweh had not kept his promise to David because the people had become sinful, and so must atone for their sins so that Yahweh will restore the covenant and send another military messiah to lead the people in great battles, destroy enemy nations, and reestablish the Kingdom of David throughout the world. The redemptive prophets of the Old Testament—Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Micah, Zechariah, and others—all called for the adoption of a military-messianic lifestyle to fight for the people’s redemption.

Simmering revolution in Palestine. The New Testament doesn’t make it obvious, but Jesus spent most of his life in the central arena of “one of history’s fiercest guerrilla uprisings.” As Roman-occupied territory, Palestine exhibited all of the classical symptoms of colonial misrule—the worst kinds of imperial and class-based exploitation and oppression. Led by “zealot-bandits”—guerrilla fighters and activists guided by Jewish ideology—the people began their war against the empire shortly before the Roman Senate installed Herod the Great as puppet king in 39 B.C.

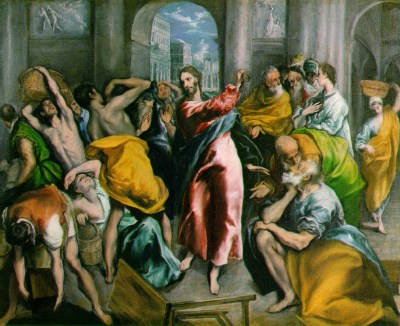

Herod, backed by the Romans, launched an almost continuous counter-insurgency campaign against guerrilla activism throughout Palestine. Upon his death in 4 B.C., uprisings took place in all outlying areas. Jesus started preaching his own messianic doctrines ca. 28 A.D. at a time when rebellions were being fought in Galilee, Judea, and Jerusalem itself. From the gospels, we know that Jesus himself led an attack on the temple ca. 33 A.D., and that another uprising led by Bar Abbas took place shortly after his trial. After Jesus was killed, more messianic leaders and guerrilla forces arose, leading to a generalized revolt by 52-55 A.D.

The fall of Jerusalem. By 66 A.D., the situation was ripe for general insurrection within Jerusalem itself, with the pro-Roman aristocratic forces and Roman troops fighting against the anti-Roman population in the city streets. In the backlands, growing guerrilla forces seized armories and stormed Roman fortresses, including Masada. Rome countered with 65,000 men and advanced siegecraft, regaining the smaller cities, executing many more military messiahs, and pushing back the rebels. In 70 A.D., Roman legions led by Titus, the son of Emperor Vespasian, finally broke through Jewish armed resistance, torched the Temple, and leveled Jerusalem to the ground. Masada was the last to fall in 73 A.D; nearly 1,000 men, women and children defenders killed each other rather than surrender to the Romans.

A long succession of failed military messiahs. Between 40 B.C. and 73 A.D., historian Josephus mentions at least five Jewish military messiahs (not including Jesus or John the Baptist), and alludes to many other like-minded guerrilla mass leaders without naming them. In 132 A.D.—60 years after Masada—a spectacular uprising led by still another military messiah, Bar Kochva, maintained an independent Jewish state for three years until it, too, was drowned in blood by a massive Roman counter-insurgency war.

John the Baptist as probable Quamranite. John the Baptist, the immediate forerunner of Jesus, is not portrayed in the Gospel as a guerrilla mass leader. These aspects of John’s work were most probably purged in the official Gospels. But the Dead Sea scrolls reveal that the pre-Christian Quamran traditions closely hewed to what we know about John the Baptist. Quamran’s sacred literature clearly reveal its military-messianic tradition, sending missionaries as vanguards for the Anointed One.

Jesus as organizer, agitator, and visionary. Immediately after John was captured, Jesus began to preach precisely among the same mass base of the Baptist (and the Quamranites). He himself assumed the same lifestyle and ideological messages. After building up a sizeable mass following in the rural areas, Jesus and his disciples led a march into Jerusalem just before the Passover holidays and began to hold massive rallies during the day, retreating into the urban underground at night, and launching at least one attack on the Temple’s business area.

More signs showing Jesus’ military messianic role. There are remnants of passages in the Bible showing that Jesus and his followers followed the military-messianic lifestyle. Some of them carried swords, and actually put up armed resistance at the moment of Jesus’ capture in Gethsemane. Later, the writers of the gospels shifted the balance of the Jesus image in the direction of the peaceful messiah; but they could not fully expunge the traces of military-messianic tradition. Even after Jesus’ body disappears from his tomb and reappears to his disciples in a vision, the uppermost question they ask him is when would he restore the kingdom of Israel. The whole Book of Revelations is full of images of Jesus’ return as an avenging military savior. Like the Quamranites, the first Jewish Christians organized themselves into a commune while awaiting Jesus’ triumphant return. In this context, it is most probable that Jesus was not as peaceful as is commonly believed, and his actual teachings and actions were merely continuing the tradition of Jewish military messianism.

Outcome of the James vs. Paul struggle. The decisive break with this tradition probably came about only after the fall of Jerusalem in 70 A.D., when the original politico-military components in Jesus’ teachings were purged by the Jewish Christians living in Rome and other cities of the empire as an adaptive response to the Roman victory. Dr. Harris goes on to reconstruct the demise of the original Jesus cult and his military messianism, which James (“the Lord’s brother”) had continued to pursue in the next 25 years, and the parallel emergence of a new image, that of the peaceful messiah—which Paul advocated among the increasing numbers of the Jewish diaspora outside Palestine. The James vs. Paul struggle for leadership came to a head during 59–64 A.D. Paul was martyred in Rome in 64 A.D. but his teachings about the peaceful Jesus continued to spread throughout the Diaspora, while the military-messianic Jesus tradition was essentially wiped out with the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 A.D.

Rise to dominance of the peaceful messiah. Scholars estimate that the first Gospel by Mark was written shortly after the Temple’s fall, now driven by factors that favored a revised image of Jesus as a peaceful messiah. From that time on, until Constantine’s conversion more than two centuries later, Christians were massively persecuted and remained a threat to Roman law and order—but no longer as a Palestine-based armed liberation movement, but as a fiscally independent (if semi-underground) international corporation that began to gain influence among the Roman upper class.

Dr. Harris ends his long essay with this richly symbolic passage:

When the Emperor Constantine took that momentous initiative [to establish Christianity as the religion of the Roman Empire], Christianity was no longer the cult of the peaceful messiah. Constantine’s conversion took place in 311 A.D. as he led a small army across the Alps. Wearily approaching Rome he saw a vision of the cross standing above the sun, and on the cross he saw the words IN HOC SIGNO VINCES–“By this sign you will conquer.” Jesus appeared to Constantine and directed him to emblazon his military standard with the cross. Under this strange new banner, Constantine’s soldiers went on to win a decisive victory. They regained the empire and thereby guaranteed that the cross of the peaceful messiah would preside over the deaths of untold millions of Christian soldiers and their enemies down to the present day.

Everyone can draw countless lessons from this timeless story. Even with the support of Dr. Harris and other scholars, I will probably fail to convince most Christians who hold every Biblical phrase as sacred, to change their views about the historical Jesus. But the lessons from this story must resonate even among those now leading the oppressed masses in waging a just war for national liberation and social emancipation. It must resonate all the way to the dangers of success, as Constantine’s victorious flag and blood-stained sword amply proves.

No doubt about it: Jesus was a visionary and revolutionary. He may or may not have led guerrilla ambushes against the Roman legion. But his message remains relevant in this place and time:

Think not that I am come to send peace on earth, I come not to send peace but the sword. (Matthew 10:34)

Suppose ye that I come to give peace on earth? I will tell you nay, but rather division. (Luke 12:51)

May I suggest that everyone interested, not merely in Jesus nor the NPA but “about the causes of apparently irrational and inexplicable lifestyles,” take a look at Dr. Harris’ book. It is also a great introduction to his theory of cultural materialism. #