This is Part 3 of a multi-part essay written for my “Pathless Travels” column. It was originally published in Northern Weekly Dispatch, 14 Aug 2005, and which I then reposted a few months later on my defunct blog hosted at Blogspot. Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, and Part 4 here.

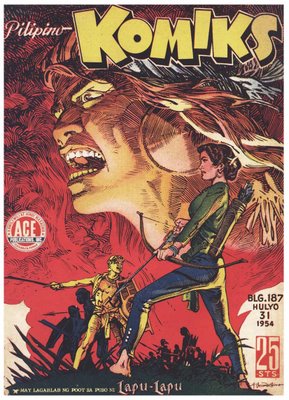

The year was 2005, and the GMA broadcast network had scored a big hit with the sword-and-sorcery TV series Encantadia. Sword battle movies were on the comeback trail worldwide, from Hollywood to China, and the genre seemed to appeal to Filipino sensitivities. But are they really unlocking insights to our own history?

In most countries, the collective past is painstakingly preserved in history books, research publications, archives and museums. There are monuments, restored ruins, tombs and landmarks, paintings and prints, bas reliefs, dioramas. There are even live and filmed reenactments, usually on the very sites where memorable events happened.

Some of the most romanticized events and figures of a nation’s history, rightly or wrongly, have to do with wars and revolutions. It is as if the emergence of a nation or hero required bloodshed, like a person’s birth and passage to adulthood.

This is understandable. After all, most nations were actually born and steeled into maturity in the throes of such violent crises. Many national heroes have emerged as leaders in such conflicts.

The problem begins, however, when the public is fed mostly with over-romanticized notions of war and combat heroics, while only the military establishment is given the chance to study real strategy and tactics. Continue reading “Romancing the sword (3)”