In the public mind nowadays, going ethnic has become hip. To wear your tribe’s gaudy colors and beads on gala occasions, or even for everyday work in provinces where ethnic diversity abounds, no longer elicits questioning stares. To declare one’s indigenous or minority roots is no longer as embarrassing as it was in earlier generations.

In fact it’s increasingly worn as a proud badge, on parade even in the halls of the United Nations in this Second International Decade of Indigenous Peoples.

Not so in the case of Aytas or Philippine Negritos. They are the half-forgotten minority among our national minorities, the most oppressed and down-trodden among our indigenous groups.

###

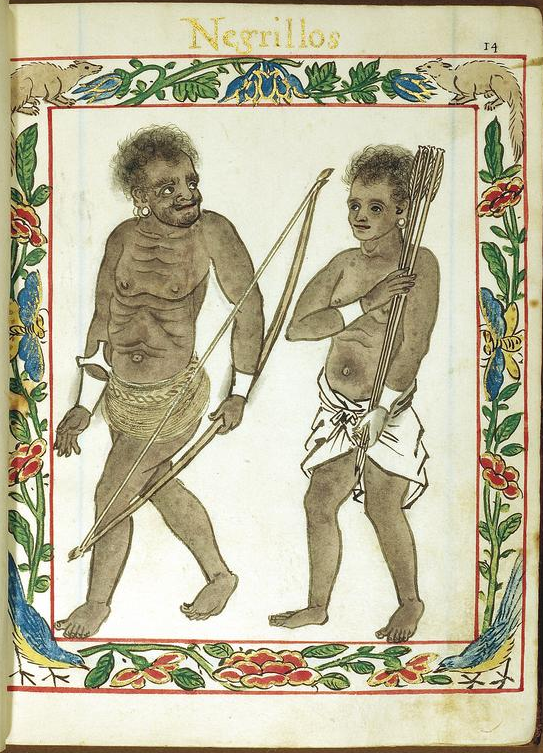

This is not only due to the Aytas’ most obvious identifying mark, which is not their costumes or musical instruments or dance styles, not their language definitely, but their very skin, hair, and body build. In a Southeast Asian brown-skin country that is insanely obsessed with dazzling white complexion, smooth shimmering hair and imposing tallness (just count the TV commercials!), we look down on the Ayta look as primitive and even alien.

No, it isn’t the Aytas’ physical features that pull them way down the minority ladder – although there’s that, too. Rather, it is that our mainstream society knows so little about them – their history, their lifeways and living conditions. Centuries of colonialism have so marginalized them, driven them into the most inaccessible forests and rugged coasts, where they still move silently in small semi-nomadic bands, that they have become near-invisible to the ordinary urban or lowland Pinoy.

Invisible, that is, until the scheme of things is disturbed by major disasters – whether of the natural variety like the Mt. Pinatubo eruption, or the man-made variety like the counter-insurgency campaign of Gen. Palparan and the globalizing impact of GATT-WTO. Then we see the Aytas in their most naked, exploited, oppressed, almost defenseless situation as they cope with the Gods Who Must Be Crazy.

###

Until I helped edit a recently completed research study, I knew only tidbits about the Filipino Ayta. How many of us know, for example, that Aytas can be categorized into some 25 major groups that are dispersed throughout the archipelago? These groups sport names like Mag-anchi and Dupaninan and Alangan.

According to pre-historians, it is more accurate to describe Aytas not as the country’s aboriginal peoples, but as the remaining descendants of Australoid groups that settled the country, with specialized physical and cultural traits highly adapted to tropical forest (mountain and coastal) conditions.

Pre-historians suggest that one ancient migration stream (with groups now called Alta, Arta, Agta) settled the northern part of Luzon and moved down the eastern part, along the Sierra Madre and Pacific coast down to the Bondoc and Bicol mountains.

Another branch (with groups now called Ayta, Atta, Ita, Ati, Dumagat, Sinauna) settled western and southern Luzon, with big remnants now found in the Zambales-Bataan mountains and Southern Tagalog foothills, while others settled what are now the islands of Mindoro, Palawan, Panay and Negros.

The Mamanwa of Mindanao, previously listed as a Negrito subgroup, is now considered a totally separate IP group.

###

Despite these researches, the government still knows so little about Ayta groups that even the National Statistics Office is unable to count their population accurately. From the NSO 2000 census, however, we can extract figures for general categories such as Aeta/Ayta (27,883), Aggay (10,258); Agta (4,558); Atta/Ata/Ati (8,846); Dumagat (14,775); and other unclassified Negrito (1,509).

Private institutions such as the Summer Linguistics Institute also try to disaggregate these population figures into still more localized groupings, including almost extinct ones such as the Arta of Quirino province (15 persons counted).

Whatever it is that statistics might tell us, one real-life observation drives home the utterly deprived conditions of the Ayta. In the Zinundungan Valley around the Cagayan-Apayao border, most Ayta individuals don’t even have family names. They don’t have birth and baptismal certificates. This means, at the outset, that they can’t even enroll their children or bring them to rural health clinics, where such documentation is required.

So every time we say that national minorities are oppressed because they are discriminated as second-class citizens and suffer from utter government neglect, think about the Aytas of Zinundungan Valley. Our country has hundreds of such small, half-forgotten Ayta valleys.#

Author’s note: This article was first published in my column “Pathless Travels” in the Northern Dispatch Weekly on 13 Aug 2006. I think it remains as relevant today as six years ago. Reposted here with minor revisions.