I’ve long wanted to write about my favorite master photographers and their philosophies. Also, having had strong opinions about photojournalism and street photography from way back, I’ve long wanted to write about the absolute need for captions.

At first I had a hard time deciding between two photographers of the 1930s-1960s era, both of world renown: Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) and Robert Capa (1913-1954). I’ve been aware of the most iconic photos of both photographers since childhood, and also their names by the time I was 12—thanks to my bookworm habits and my parents’ sizeable library.

Both Dorothea Lange and Robert Capa also represent two related genre that have preoccupied my many years as amateur photographer: those of photojournalism and documentary photography.

I had written about Capa earlier, in a piece about my obsession with wars. But I realized that writing about Lange, for me, also meant writing about photo captions in a most profound way. It was like shooting, um, two scenes in one frame.

I had long idolized Capa, and for many years I treasured a thick two-volume collection of Reader’s Digest articles on World War II that contained many of his combat photos. His coverage of the Normandy landings on D-Day was nonpareil. Sadly, he was killed by a landmine in Vietnam at the young age of 41.

Nevertheless, I chose to prioritize Lange because the social philosophy behind her documentary photography, especially her most positive attitude to captions (including the concept of General Caption that ties together a group of photos), was more fully articulated and closely resembles my own thinking. She certainly lived much longer than Capa, so had more time to digest and share her lifelong experiences.

Lange and the FSA

As a young woman in the 1910s and 1920s, Lange was first an apprentice to well-known New York photographers, then moved base to California where she built a career in doing portrait photography among the elite. But then the U.S. economy collapsed during the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, ravaging and uprooting millions of households.

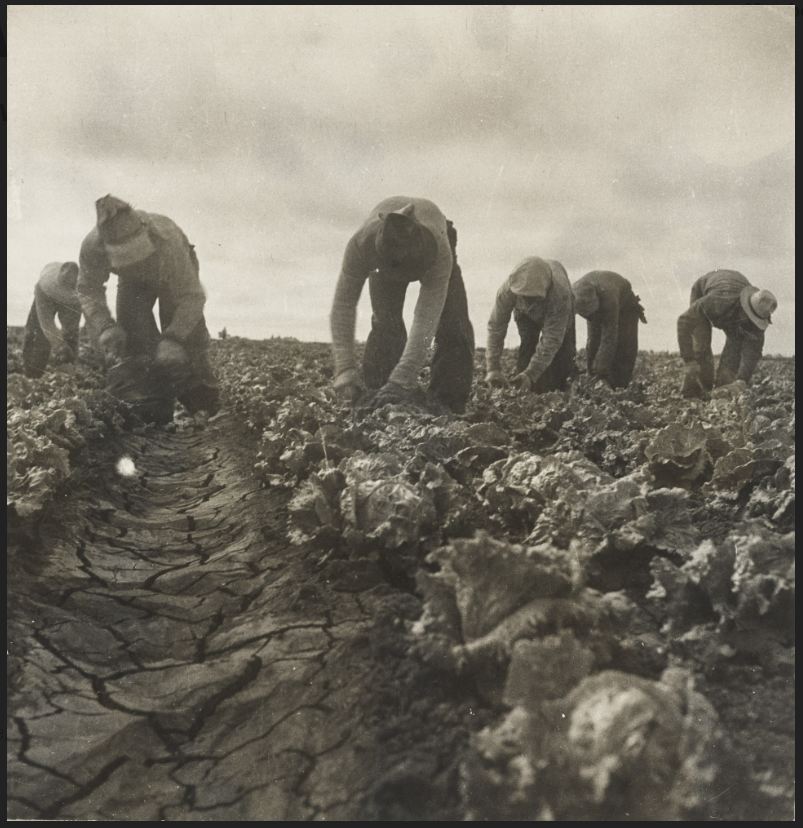

By 1933, Lange’s profession took a turn towards documenting the extreme poverty, labor abuses, racism and environmental destruction throughout America—especially among the rural poor and migrant workers.

In 1935, she began work for the California State Emergency Relief Administration (later RA, becoming the Farm Security Administration, or FSA, in 1937), which was doing a photodocumentary project on the situation of the rural poor.

Lange travelled across the U.S. West Coast, South and Southwest, not just to take photos but, more importantly, to undertake social research for the FSA together with other artist-photographers and documentors.

Her combined work of seeking social justice and honing the power of photography continued throughout her life, even during World War II when she documented the controversial internment of Japanese Americans, a U.S. Government program which she criticized.

Lange’s work, especially her extensive and critical captions, were often suppressed in earlier decades, in what she saw as “the decontextualization of her work.” Only in 2008 were many of her field notes published.

Nevertheless, her achievements are now well-recognized. She has been inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum (https://iphf.org/inductees/dorothea-lange/), among many other honors and awards.

Lange’s deep philosophy on photo captions

Like I said, I chose to highlight Lange’s philosophy and practice of documentary photography because I believe in a similar approach, including her attitudes about getting close to her subjects in their everyday life, interviewing them, and including as much information as possible in her captions and other accompanying documentation.

Ever-critical of purists who tried to avoid any line of text, she insisted just before her death in 1965: “All photographs—not only those that are so called ‘documentary’…can be fortified by words.” (MoMA, 2020) “What the right words can do for some photographs is enormous.” (Meadows, 2016)

Lange viewed her work with the FSA as that of a “visual sociologist, a discoverer, a social observer,” pushing documentary photography “further than social realism” and thus blending art and social science. “Every photograph… belongs in some place, has a place in history—can be fortified by words.”

She took extensive field notes, “which evolved into a General Caption, crafted with observations, interviews, and economic data to work with a series of photographs curated to tell a story.” (Meadows, 2016; MoMA, 2020)

It wasn’t Lange, but Ben Shahn—another photographer-artist who also worked for the FSA, and another one of my childhood favorites—that invented the concept and practice of the General Caption for his own photos of rural Ohio.

But Lange perfected it. She edited both photographs and captions to complement each other as a unified narrative. She gave detailed backgrounds of her subjects. Thus, the captions both expanded the meanings of her photographs and made them very specific.

In June 1939, Lange helped sociologists at the University of North Carolina explore “how photography could augment other research methods.” As Meadows (2016) summed up her contribution: “The FSA photography project … archive holds more than 165,000 photographs—perhaps the best example to date of the use of photography as a tool for social research.”

I wish that photography courses include more developed modules on the social roles of photography, especially on its being combined with journalism, documentary, and social research and commentary. Lange’s contributions to this field must not be forgotten or just left to individual study initiatives.

A sampling of Lange’s photography

For now, however, here is my modest selection of Lange’s photographs. The captions are not mine; they are directly taken from the websites which hosted her various photo collections: Context.org (Meadows, 2016) and MoMA (MoMA, 2020; MoMA, n.d.)

Lange, Dorothea

Photo 2. General view of a hillside farm which faces the road showing owner’s house, outbuildings, and tobacco field howing erosion. The Negro sharecropper farm is on the other side of this same hill. Person County, North Carolina.

Photo 3. Young sharecropper and his first child. Hillside Farm. Person County, North Carolina.

Photo 4. Wife and child of young sharecropper in cornfield beside house. Hillside Farm. Person County, North Carolina.

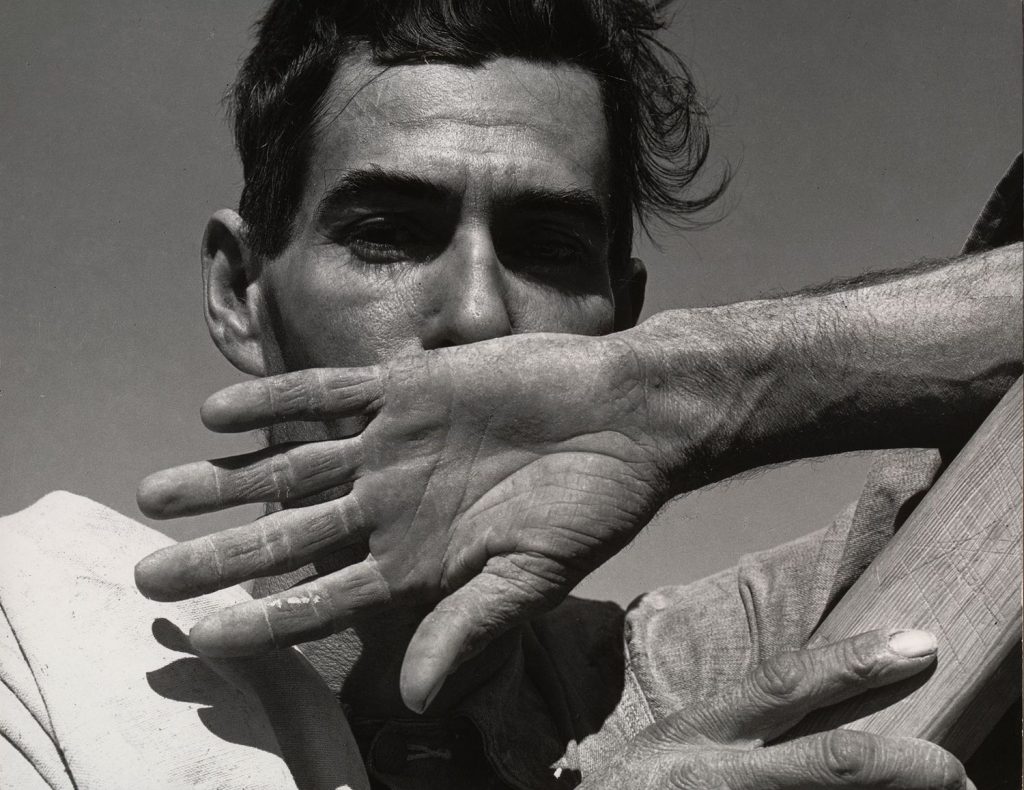

Photo 5. Migratory Cotton Picker, Eloy, Arizona. November 1940. Gelatin silver print, 19 15/16 × 23 13/16? (50.7 × 60.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Photo 6. On U.S. 99. Near Brawley, Imperial County. Homeless family of seven, walking the highway from Phoenix, Arizona, where they picked cotton. Bound for San Diego, where the father hopes to get on the relief because he once lived there. Library of Congress Image: Call Number: LC-USF34-019075-E [P&P] in 1939. (Date: February 1939)

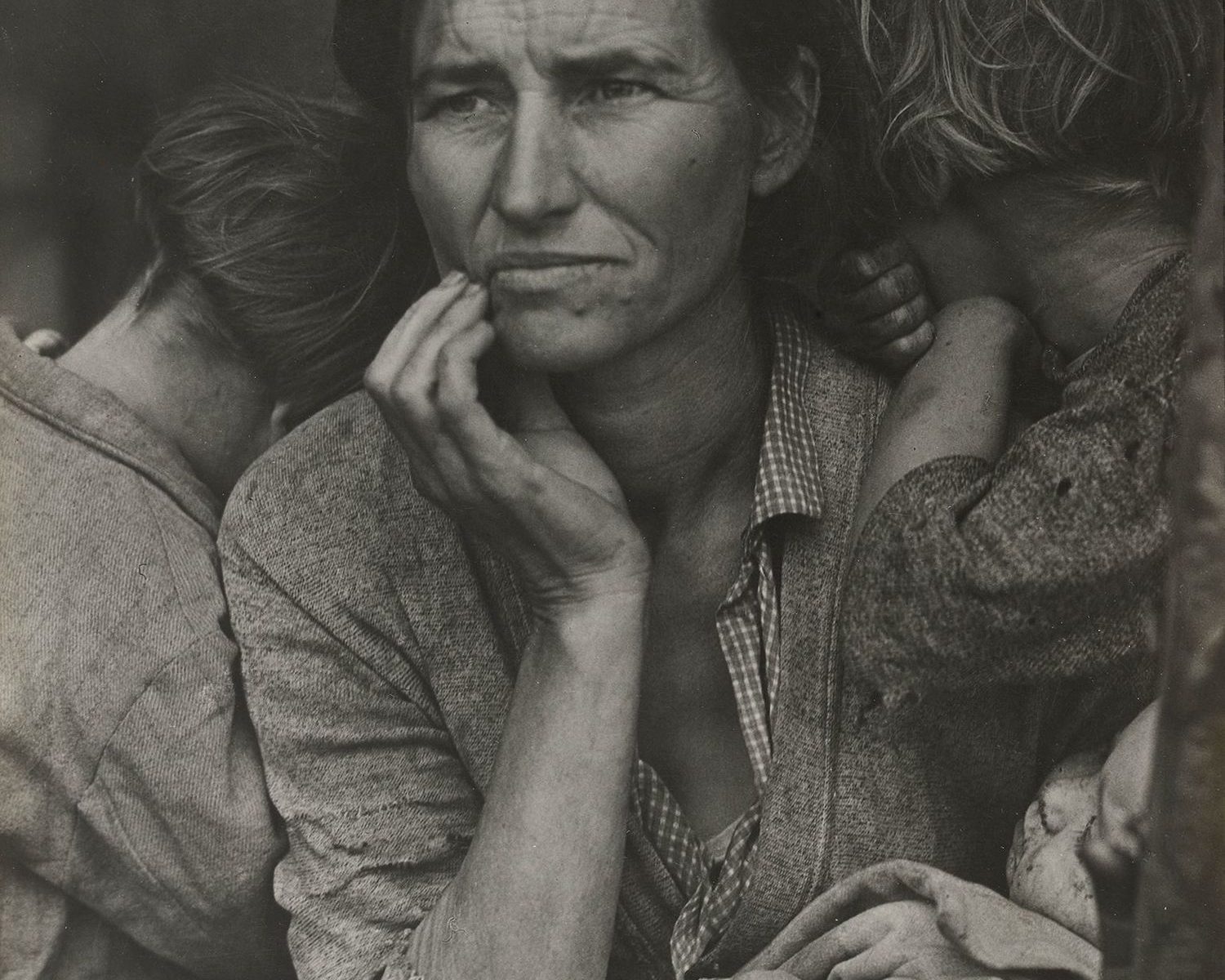

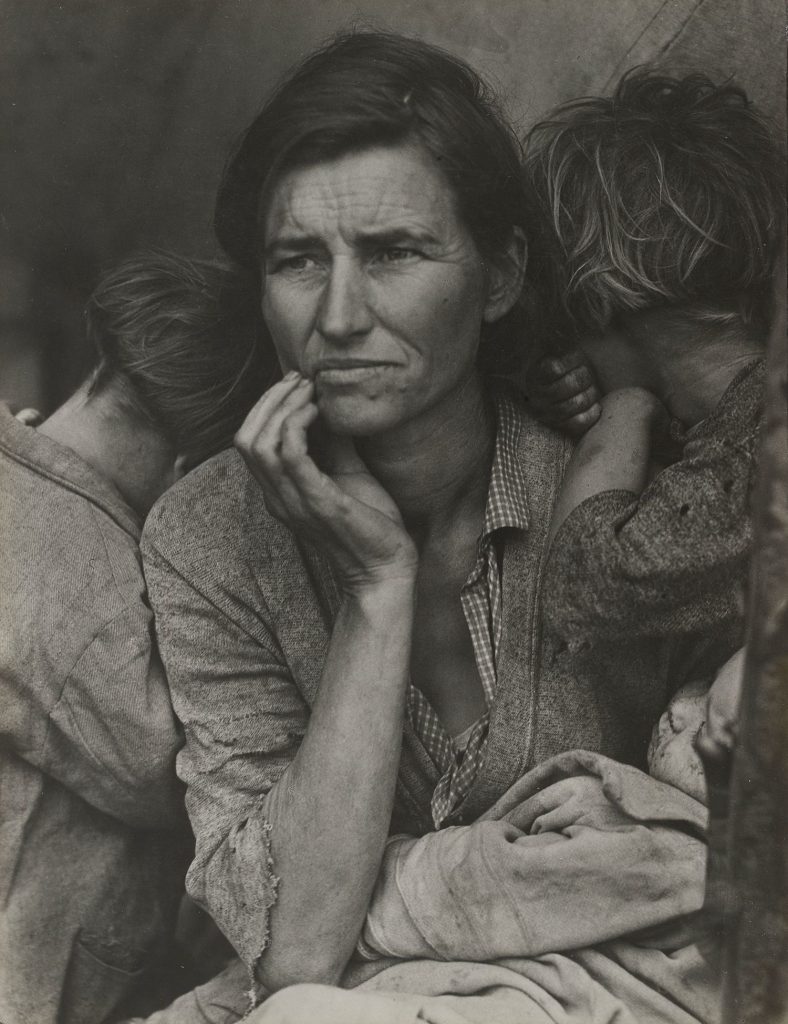

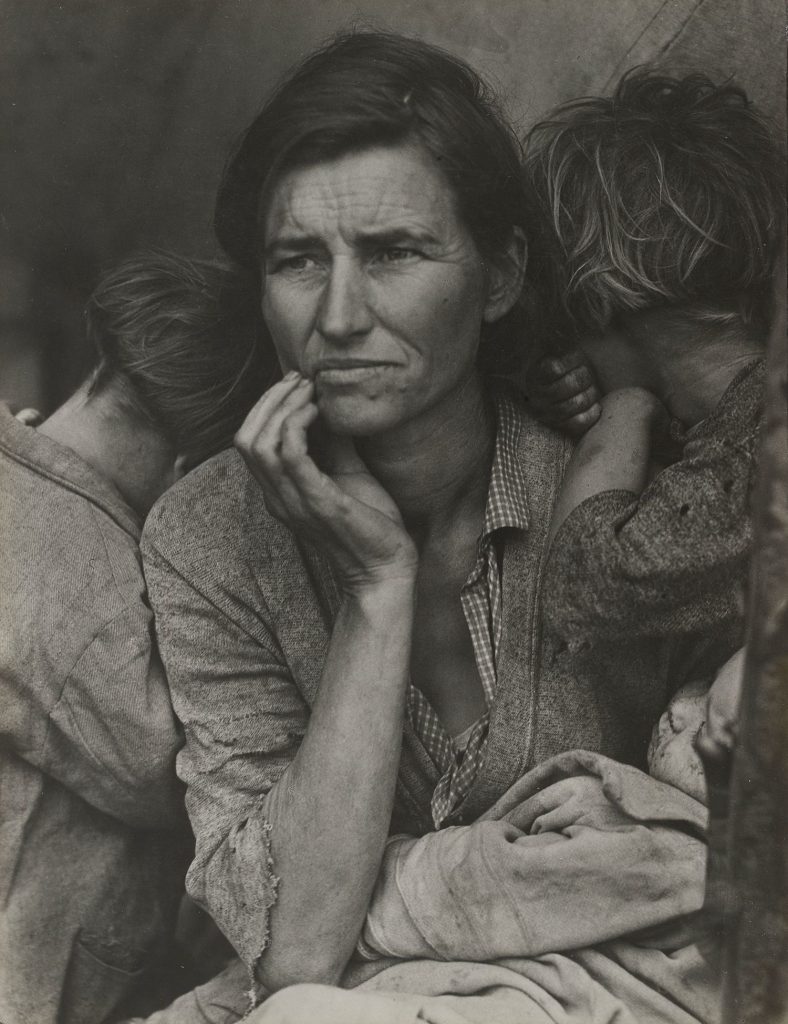

Photo 7. Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California. March 1936. Gelatin silver print, 11 ? x 8 9/16” ( 28.3 x 21.8 cm ). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. That fateful day, Lange drove past the sign “PEA-PICKERS CAMP,” then decided to return as if drawn to a magnet. She saw and approached a “hungry and desperate mother, [who said] that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding field and birds that the children killed.” Lange took seven camera shots of the woman, Florence Owens Thompson, in various poses with her children. One of these shots, at first titled “Pea Picker Family, California” and later retitled “Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California,” became a symbol of the Great Depression.(MoMA, n.d.)

REFERENCES

- Iconic Documentary Photographers. (n.d.). All About Photo website. Retrieved May 6, 2023 from https://www.all-about-photo.com/photographers/documentary-photographers.php

- Carol Quirke. (2019). Dorothea Lange, Documentary Photography, and Twentieth-Century America: Reinventing Self and Nation. Academia site. https://www.academia.edu/38635931/Dorothea_Lange_Documentary_Photography_and_Twentieth_Century_America

- Lloyd, F. (2023, February 15). Photojournalism- Robert Capa and Dorothea Lange. NoticEverything website. Retrieved May 5, 2023 from https://noticeverything.wordpress.com/2023/02/15/photojournalism-robert-capa-and-dorothea-lange/

- Martyn, J. (2013, May 10). International Documentary Photography. Martyn Jolly site. Retrieved May 7, 2023, from https://martynjolly.com/2013/05/10/international-documentary-photography/

- MoMA. (2020). Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures. Retrieved May 6, 2023 from https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/5079

- Dorothea Lange. (n.d.) National Women’s Hall of Fame. Retrieved May 5, 2023 from https://www.womenofthehall.org/inductee/dorothea-lange/

- The Art Story. (n.d.) Documentary Photography. The Art Story website. Retrieved May 6, 2023, from https://www.theartstory.org/movement/documentary-photography/

- Visual Arts Cork. (n.d.) Documentary Photography (1860-present). Visual Arts Cork website. Retrieved May 6, 2023, from http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/photography/documentary.htm