Author’s note: This was first published on 18 May 2003 under my Pathless Travels column published by Northern Dispatch (Nordis) Weekly. I’m reposting it here in three parts, with some revisions to update my own understanding of the issue, and to make it more timely. This is Part 3. Read Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

Again, let me wonder aloud: Why is it that despite the evidence to the contrary, the twin myths of a “Pinoy summer” and a “Pinoy rainy season” persist in the public mind?

In the same light, one wonders about the stubborn persistence of those other undying myths, about Filipinos for example having descended from “three waves of migration” — you know, the fantastic but now-debunked story about Indonesian A and B, then Malay, that many of us still believe as true.

Or how about the Code of Kalantiaw, which has been shown to be a hoax? Let’s mention too the story of the Ten Datus of Borneo, which is a folk legend that might have some historical basis but with no hard evidence so far. Or the myth that there is only one Philippine language, or five or eight at most, while the others are merely “dialects.”

One reason for the persistence of these long-standing false notions has to do with defects in our educational and mass media system, which are too many and complex to jot down in a couple of paragraphs. These defects all tend to mix up fact and myth, truth and fabrication, evidence and speculation, the part with the whole.

But then again, perhaps one other underlying reason is that we as Filipinos simply want to satisfy our deep patriotic hunger for things held in common as a nation, for truly national attributes, tapping on even the flimsiest sources of national symbolism, and thus transcend the variable effects of our diverse ethnic roots, stormy colonial past, and fierce class conflicts.

The late historian William Henry Scott implied this much, in his insightful comments about our seemingly hopeless infatuation with such fanciful theories as Beyer’s “waves of migration” or with such outright hoaxes as the so-called Code of Kalantiaw. And–may I add–why we keep falling for that barbershop tale about the fluorescent lamp being invented by a Filipino named Agapito Flores.

Maybe that’s also the reason why many Metro Manila-oriented media and culture practitioners are too quick to conclude for all Filipinos and the Philippine in general what might be a valid experience in the national capital region, or for its middle class residents.

Maybe we all want to believe that all Filipinos, despite varied geographic, cultural, ethnic, class, and occupational backgrounds, can still hold on to a core of collective experiences–real or imagined, for good or bad. Thus, EDSA is not just a very long and circuitous avenue around Metro Manila, but an outraged people’s collective spirit of revolt.

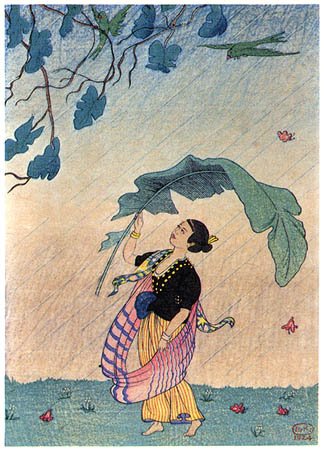

Thus, too, must we try to understand why a writer for a national magazine fresh out of college would so innocently write, “It’s almost June again, folks, start of the rains, time to go shopping for the latest rainy-day fashion wear…” She will do so in the most cheerful manner, blissfully oblivious of the fact that some Mindanao and Cagayan Valley communities have been battered by heavy rains accompanied by floods late last year and early this year–before the so-called “Pinoy rainy season”–and couldn’t care less if they drowned in fuchsia or chartreuse-colored raincoats.

Mind you, I’m trying my best to understand the collective psyche that underlie our continuous myth-making, which in turn exerts a powerful influence on our daily mental habits. But I do hope our media and cultural writers take time to read more about ground-level realities, become more critical, or at least listen to more critical voices. Otherwise, we will all drown in fuchsia-colored raincoats.

###

“Seryoso ka unay itatta a! (My, we are so dead-serious today)” Kabsat Kandu comments, with a bemused smile on his face. “You should also write about community climates,” he adds. “For example, why does it rain often here, but when I go down to Baguio, it’s hot and dry as hell?”

I nod in agreement with my neighbor despite his slight hyperbole, and mentally take note to research about the fascinating world of micro-climates. Why it’s always a bit more rainy on the leeward side of mountains. Why Mount Pulog has a bald top. And why urban forest parks are cool and easy.

By the way, it would be interesting to see how much of these regional and local climate patterns are reflected in the native languages of our country’s different localities. Tag-ulan or panagtutudo (rainy season), tag-araw and tagtuyot, or tikag (dry season) are the most obvious terms. For farmers and fisherfolk, amihan/amian (north wind, northeast monsoon), habagat/abagat (south wind, southwest monsoon), and siyam-siyam/nepnep (continuous monsoon rains) are also of practical use. I do wonder how many of us still know what specific native weather terms mean, like ihing-langgam and balak-laot.

A lot of indigenous climate and weather lore is still out there, thriving as rich oral traditions kept alive by farming, fishing, and other rural communities that continue to live close to nature.

I hope more feature writers, whether fresh out of college or not, get some sense into their heads to interview our farmers and fisherfolk about these things more often, even as they do the obligatory pieces about white-sand beaches, Santacruzan beauties, cold drinks to beat the summer heat, and gearing up early for rainy-day fashions.

###

“Hey, the rain stopped too soon,” Kabsat Kandu noted. “My water drums are only a quarter full yet. Not fair!”

My neighbor is right again, of course. It’s not fair. After all, who’s to say what’s “fair”–sunny or rainy weather? In the meantime, nevertheless, let’s all enjoy what’s left of the so-called Pinoy summer before the so-called Pinoy rainy season blows in. #