I have this lifetime obsession with boats.

I secretly spend a huge amount of time reading and writing about watercraft of all types. I enthusiastically ride them every chance I get—from the rakit (pontoon barge) of many Abra River crossings in my childhood and youth, to the modern inter-island passenger ships that ply the southern islands from the Port of Manila, which I’d usually choose over airplane rides.

This obsession always generates two persistent streams of thought: On one hand, my artistic (okay, melodramatic) side is hypnotized by the rippling, churning, foaming, almost magical flow of the sea or river in the wake of the boat. It’s a hypnotic feeling that rarely bores me.

On the other hand, my technical side (verging on steam-punk) always drives me to ogle and inspect up close the engine, the machinery, the mast and rigging that actually make the boat turn, stop and go, and find out the hows and whys. It’s an obsession that surpasses the artistic one.

###

From this technical viewpoint, one curious but important observation emerges:

Most Philippine boats are not mass-manufactured or fabricated according to shipyard standards. They’re not like your usual freight trucks bought from a dealer that reconditions imported used trucks from Japan. Rather, most vessels classified as banca or motor banca are built in small, often impromptu, boatyards.

“I don’t see any boatyards nearby.” Kabsat Kandu asks.

That’s understandable, coming from my pesky neighbor who is, after all, “a proud highlander, thank you.” Maybe such boatyards are invisible to most of us because they are scattered from Aparri to Jolo, often literally on the beach itself, in so many seaside towns, wherever there is access to inland suppliers for parts.

These bancas range from tiny dugouts used by poor fisherfolk and farmers for moving along inland rivers and swamps, to municipal 10-meter-long fishing boats running on truck engines, all the way to inter-island double-deckers that can ferry 100-200 passengers from the Batangas City port to MIMAROPA islands, or those that ply the regular Surigao-Dinagat-Leyte route.

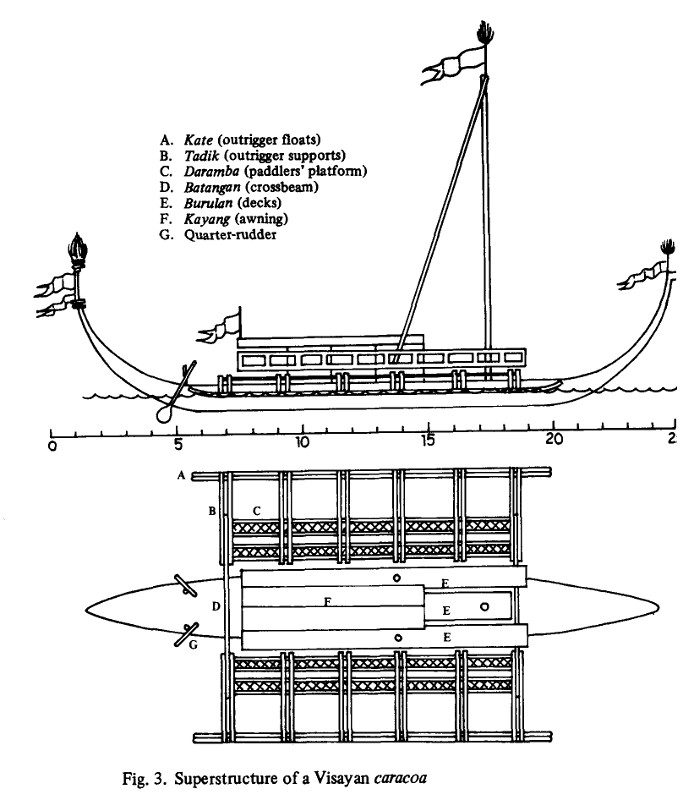

These bancas have hulls constructed of wood (sturdy planks and marine plywood), with combination wood-and-bamboo outriggers and superstructure. They run on a wide range of engines (usually diesel), transmission, and shaft-propeller assemblies. They are fabricated by local carpenters and mechanics who more often than not receive their training the traditional way: from master to apprentice, from father to son. Our islands teem with them by the tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands.

###

There are government regulations and standards to follow, yes. Banca builders are supposed to be registered. They are supposed to submit their banca designs and sketches for MARINA’s approval before they start building. But boat-building is a Filipino tradition that is as old and stubborn as building a rural house—we build them as we know how, regardless of requirements for architect’s plans and building permits.

There are hundreds of ingenuous ways by which engines and power trains, originally designed for land vehicles, have been adapted by us for watercraft, complete with locally designed steering, throttle, and other control mechanisms.

Try to take a seat, as I often do, right behind the banca pilot and close to the engine, where it is noisiest and least comfortable, and where it reeks of fuel oil. I have seen bare-bones steering wheels (cannibalized from trucks) that operate rudders through tightly-wound nylon cordage; tin bottle-caps nailed to the pilot’s panel, regulating throttle speed through thin wires bought from a hardware store; and assorted gallon-size containers for on-the-fly refueling and engine-cooling.

(For a sampling of Internet blogs and discussions around the oido way of building boats, see for instance http://duckworksmagazine.com/03/r/articles/banca/index.htm and http://indigenousboats.blogspot.com/2011/07/philippine-bancas.html.)

###

This point is not surprising, really—considering our country’s thousand years of water-borne traditions. After all, it is a central element in our collective myth that our ancestors came ashore on boats called balanghai, and that our boat culture went on to shape the spread of our pre-Spanish communities.

One of our proudest archeological discoveries—the so-called “Butuan boats”—are now on display at the National Museum and at the Balangay Shrine in Butuan City. These have been carbon-dated to as early as 320 CE. (Source: Ligaya S.P. Lacsina, “Traditional island Southeast Asian watercraft in Philippine archaeological sites.”)

The sea-faring abilities of these ancient boats have been proven, among other things, by a recent “Voyage of the Balangay” project in which working replicas of the balanghai, partially modeled after the Butuan boat and built by indigenous Sama-Badjao boat builders, were able to sail throughout southern Philippines and other destinations in Southeast Asia.

The deep roots of our people’s boat-building and sea-faring traditions have been explored by several researchers and writers. The most thorough and engaging studies have been by William Henry Scott, who wrote “Boat-Building and Seamanship in Classic Philippine Society” in 1982.

###

The Spanish and American regimes press-ganged succeeding generations of Filipino boatbuilders and seafarers to work in the foreign colonizers’ shipyards, big docks and naval vessels. From Manila, Cavite, Bataan and Zambales, our ancestors were able to reach Guam, Formosa (now Taiwan), Mexico, Louisiana, Hawaii and California. They came in, shackled as corvee laborers and later as bonded laborers.

Despite this, we have been able to preserve our own marine traditions, and even innovate and combine old and new technologies—a typical Pinoy trait. We did so with jeepneys, tricycles, kuligligs. And so we are doing the same with boats and sea travel.

Living in an archipelago of 7,100 islands with one of the longest coastlines in the world, our people have no choice but to develop our domestic boat industry, and on that foundation, our strategic ship-building industry. That is our only viable option, if we want to build our nation’s capacity, defend our national territory, protect our most outlying islets and shoals, and maximize our exclusive economic zone.

Our boat industry is even now thriving in many respects. But it must not depend on foreign technology, at least not wholly, and not permanently. A greater future awaits, if only the government and key private-sector stakeholders adopt a correct strategy and depend on the people’s creativity and grassroots entrepreneurship.

###

“Okay, okay, but I’m interested in the next Voyage of the Balangay project,” my friend Kabsat Kandu says. “If it docks at San Fernando and recruits trainees for sailing to the Spratlys, I’m signing up.”

Well, I haven’t heard such plan. But other naval powers such as the U.S. and some European countries have been doing just that: build and maintain traditional sailing ships, then use them as naval training vessels for “youth development, maritime education, marine scientific research and coastal community outreach.”

“The Philippines doesn’t have anything like that?” he asks. “In that case, I have decided at this very moment to build my own balangay and mobilize volunteers to sail it to the Spratlys.”

“Hmm, good idea,” I reply tactfully. “But it would be a good first step to plan something more realistic and immediately fruitful. For example, there are projects to help Yolanda-affected coastal communities in Samar-Leyte and Panay. You could apply as a volunteer boat-builder.”

Kabsat Kandu pores through my files. Hopefully, our conversation has made him a new convert—to this lifetime obsession with boats, I mean. # Follow @junverzola